by Diane B. Smith

Morss Tannery — Ledgedale was first settled in the 1840s when Burton Morss built a water-powered tannery along the Wallenpaupack Creek on this site. Morss was a third-generation tanner whose family had operated tanneries in the Catskills until the vast hemlock forests of the “great sole leather district” of New York State were finally depleted, forcing tanneries there to close. In search of new sources of tanbark, Morss and other tanners moved their operations into the magnificent forests of northeast Pennsylvania.

There is not region anywhere better supplied with forest than Pennsylvania. A large part of this forest is so rugged and mountainous, and so covered with rocks and stones, that it cannot be cultivated and will therefore always remain.

—PA State Bureau of Statistics

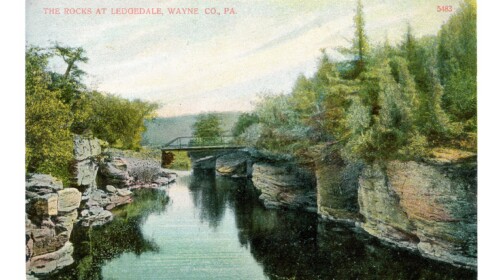

Ledgedale was an ideal location for Morss’s new leather-tanning enterprise. The surrounding hemlock forests of Greene and Salem Townships provided a rich supply of tanbark needed for producing the leather. The tumbling waters of Wallenpaupack turned the wooden wheels that powered the various mills, and the creek provided ample water for the water-intensive leather-tanning process. The creek was dammed upstream to create a mill pond and race to divert water to the sawmills, bark mill and gristmill. On the downstream side, it carried away the used liquors, lime solutions, and other caustic chemicals. Unfortunately, these byproducts had a detrimental effect on the environment, polluting the streams and producing harmful odors. In 1876 the State enacted a law that required tanners to prepare a holding tank for sediment, refuse, tanbark and tanning liquors to prevent it from passing into the Commonwealth’s waterways. Penalty for violators was fifty dollars for each offense, in addition to liability for all damage done.

A village sprang up around the sprawling tannery site, and at first it was called “Tannerytown.” A company store, gristmill, blacksmith shop, two one-room schoolhouses, and St. Mary’s Catholic Church were built on the Wayne County side of the creek. Across the bridge in Greene Township Pike County, were a general store, a shingle mill, a cider mill, and three one-room schoolhouses, all within a mile of Ledgedale. According to the 1850 census, the tannery employed 90 workers in occupations such as tannery boss, tannery foreman, day laborer, bark peeler, handler, scrubber, beam hand, sweater, yard hand, bark grinder, lumberman, sawyer, millwright, carpenter, teamster, clerk and boatman. Many of the workers were newly arrived Irish, Polish and German immigrants. Some lived in company housing and others purchased land nearby and established family homesteads. The Ledgedale Post Office was established in the company’s general store in 1863, and mail arrived by stagecoach three times a week, Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday evenings. Burton’s son Leonidas Morss was appointed postmaster, a position he held until the post office was closed in 1888.

Ledgedale was a booming town in the 1870s and 1880s. Up to 30,000 hides were processed at the tannery each year. Animals hides preserved in salt were shipped from South America to New York City and then to Honesdale where they were loaded on canal boats and taken to Hawley. The hides made the final leg of their long journey by steamboat to the tannery. The finished leather followed the same route in reverse to city markets. At the time Wayne County had the largest tanneries in the world, and the Ledgedale Tannery ranked second in earned income out of the county’s 19 tanneries. The leather it produced was valued at $44 million in today’s money.

Tragedy struck in the spring of 1880 when the Ledgedale Tannery was nearly destroyed by fire. At that point, Burton turned the business over to his son Leonidas, who began rebuilding immediately. By fall the new, modern tannery was nearly completed. The main building was 400 feet in length, and the bark-mill and leach house were 150 feet, double their previous size. New machinery was installed in the buildings, and a steam engine would now power most of the work. The 40’ x 70’ boiler house was built of stone instead of wood, as were the furnaces. The 100-foot chimney was made of brick. The tannery now employed about 200 people, many of them Irish immigrants. It consumed 5000 cords of hemlock bark a year and turned out 50,000 sides of the finest sole leather. Boots made from hemlock-tanned leather never leaked!

However, as the Morss family well knew, leather tanning is a fleeting industry. Due to the dwindling supply of hemlock, the number of tanneries in Wayne County declined over the next decade from 19 at its peak to just five. When the Ledgedale Tannery burned a second time in 1892, it was never rebuilt. Newspaper accounts of the day noted that the loss was a severe blow to its employees. In 1896 the Shoe and Leather Reporter, the most important industry magazine, concluded an article on the closing of the tanneries in the Poconos with these words, “Nothing now remains of the tanneries but the ruined vats. The hemlocks are gone, but there are pleasant memories all through the region of the free-hearted and free-handed tanners of the old times.” When Burton Morss died in 1884, it could be said that he came into the sparsely settled Wallenpaupack Valley, built a tannery, a town, and a fortune and, in the process, he removed a wilderness.

Morss Gristmill — Leonidas Morss, like his father before him, managed several business enterprises. In addition to the tannery, he owned the largest farm in Salem Township, where he kept 200 dairy cows and 200 head of cattle. Like bark, hay was expensive to ship, and all of the hay and grain consumed by the animals was grown on his farm. The Morss gristmill was a natural extension of his farm. Appearing for the first time on the 1870 Industry Census, the mill had an undershot waterwheel, which powered three runner stones and produced an average of 8500 bushels of grain each year. By 1880 the mill had been refitted with five water turbines and production capacity had increased to 300 bushels of flour or feed per day. Half of the flour ground at the mill was sold on the market, and the other half was ground for farm families who lived nearby and brought their grist to the mill.

After the tannery closed in 1893, the gristmill remained in operation for another two decades. From that point, all of the work was probably custom, as the mill continued to serve the needs of local farm families.

Fletcher took a grist to the mill at Ledgedale. 125 lbs. of flour. —Margaret Hazelton’s diary, April, 1906

Fletcher went to Ledgedale for the cider that he left the apples there for yesterday. They make the cider nights for there is not enough water for both grist and cider. —Margaret Hazelton’s diary, October 23, 1908

By 1912, the dam and millpond were no longer usable and the mills operated only in spring when the water in the creek was high enough to fill the millrace. The mills and the general store remained until work began on the construction of Lake Wallenpaupack in the mid-1920s. The gristmill was dismantled and sold to a mill owner in Tatamy where it was restored and made operational once again. The remaining buildings, including the last of the tannery buildings, were either demolished or dismantled and sold to area residents. The tannery manager’s house, a worker’s house and remnants of the mill race are all that remain today. The Ledgedale Cemetery located in the nearby Indian Rocks Community Association is the resting place of many of the immigrants who worked at the tannery.

Lake Wallenpaupack — In the early 1900s engineers recognized the potential benefits of damming the Wallenpaupack Creek to create a reservoir for the purpose of producing hydroelectric power. The Pennsylvania Power & Light Co. (PPL) began planning for the project by purchasing land from local residents on both sides of Wallenpaupack Creek from Ledgedale to Hawley. Approximately 12,000 acres of land were acquired from about 100 landowners at $20 dollars an acre.

In preparation for the building of the dam and the flooding of the valley, homes, farms, shops, barns and outbuildings were demolished or removed. Forests were cleared, leaving behind the stumps.

In order to create Lake Wallenpaupack, PPL constructed a dam on Wallenpaupack Creek at Wilsonville. Wilsonville was named for Judge James Wilson, who was a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, a Supreme Court Justice, and an early landowner and farmer on whose land the village was founded. The entire village was razed and the site is now under the waters of the lake. In all, 17 miles of roads and utility poles were rerouted, and Purdytown cemetery had to be relocated.

The Wallenpaupack Dam Project took two years to complete. Nearly three thousand men were employed over the course of the project. Once the dam was complete, it took seven months for the reservoir to fill. For many years after the lake was opened, the water remained so clear that the foundations of buildings and the forest of tree stumps were visible under the water.

The lake was officially opened to the public on July 31, 1926. Original state permits for the lake required public access areas to the lake, so recreation was on the minds of the regulators from the beginning. PPL established four parks to provide facilities for camping, sightseeing, picnicking, boat launching, and fishing to enhance public use of the lake. These parks were located at the lake’s southern end (Ledgedale and Ironwood Point) and the lake’s northern end (Wilsonville and Caffrey Landing). Early campers set up surplus World War I army tents on wooden platforms near the water. As interest in camping increased, the temporary wooden platforms were moved in the late 1950s to the Ledgedale area in Pike County. Moving the campsites allowed for more day-use areas and services for the campers.

Electric service was provided to campsites along with new facilities such as toilet, laundry and shower buildings. The grocery store was enlarged, and, more importantly, living quarters were provided for a resident Park Director. The name was changed to Ledgedale Recreation Area, reflecting its expanded use.

Recreational use was limited at first, but after World War II that began to shift as roads improved, travel became easier and leisure time increased. In the 1960s and 70s, the burgeoning second home industry led to a dramatic increase in the number of people engaging in water-related activities on the lake.

Today, Lake Wallenpaupack is one of the nation’s most popular lakeside recreational spots. The third largest lake in the state with almost 6,000 acres of fresh surface water, it is ideal for water sports—sailing, boating, swimming, water-skiing, fishing, and in winter, ice skating and ice fishing. The natural beauty of its setting in the midst of the Pocono Mountains makes it an attraction for outdoor activities all year round.

Sources: