by Diane Smith

School was out, my parents had signed my working papers, and I was about to start my first summer job. In those days, there were dozens of summer boardinghouses operating in the Poconos, and several within a few miles of home. They had names like Summit Farm, Valley View, Timbertop, Mountain Rest, and Hillcrest. It was the first week of June, and they were all hiring.

Mom suggested I contact Hans and Sophie Michl, owners of Panther Lodge and members of our church. Their daughter Hilda had been in my Sunday School class at Saint Mary Magdalene’s. Hans and Sophie welcomed me into their fold and said I could start right away as a chambermaid/waitress trainee. Mom took me shopping in Scranton and I picked out a couple of plain white waitress uniforms, a box of nylons, and a pair of comfortable shoes—thick-soled lace-ups in solid white, styled a lot like my aunt Ethel’s everyday shoes.

Although I was not aware of it at the time, I had been living a life pretty much free of domestic responsibilities—setting and clearing the supper table, a little baking, a little dusting, and that was about it. I could iron a blouse in a pinch. Mom gave me a crash course in proper bed-making (she herself had worked at the Fern-Dell as a teenager), and carefully demonstrated how to make tight hospital corners, fold down the top sheet exactly four inches, and roll the pillows in the bedspread to make a neat bolster against the headboard.

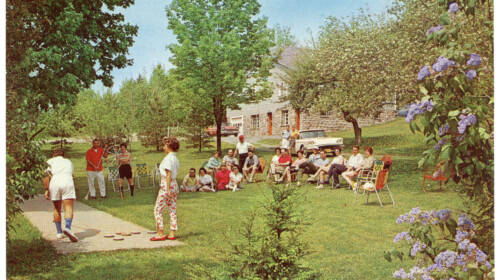

Panther Lodge opened for the season on Memorial Day weekend, and by the Fourth of July it was booked solid. The main house, originally a farmhouse, had six rooms upstairs furnished with old-fashioned cast iron double beds and high-backed oak dressers. When Hans and Sophie ceased farming in the late 1940s, Hans converted the bank barn to a guest house with rooms where the hay mows had been. They were decorated in mid-century modern and had windows that overlooked Sugar Hill Creek in the valley below. The barn’s lower level was transformed into a recreation room where guests played pool, bridge and mahjong. With its thick stone walls set into the hillside, it stayed cool even on the hottest days. Hans added a second guest house, an in-ground swimming pool, and shuffleboard courts. Altogether, the Lodge could accommodate up to 50 guests. Some families would stay all summer. The husbands worked in the city during the week and came up on the weekends, traveling by train to Cresco Station where Hans would pick them up.

The full-time waitresses that summer were Hilda Michl, recently married, and Sandy Rohrbacker, who was starting college in the fall. They made waitressing look easy. Even better, they were cheerful, patient and fun to work with. On Hilda’s and Sandy’s day off, and on weekends when the resort was full to overflowing, I would help in the dining room. I learned how to stack and ferry heavy trays back and forth, memorize orders without writing anything down, and carry six plates at a time. Serve from the left, clear from the right. There were two swinging doors into the dining room, one for each waitress, and it only took one crash to learn always to use the correct door.

Our day began at 7:00, and by then the kitchen was already bustling. Sophie was up each morning at dawn to begin the baking—sticky buns, cinnamon bread, crumb cake. It was our job to make the oatmeal and the coffee on the auxiliary stove in the kitchen. Breakfast was served from 7:30 to 9:00, and it was announced by walking up and down the hallways ringing a brass handbell, the kind that one-room schoolteachers used to call the kids in from recess. They must have hated us!

Sophie did all the cooking and baking. There was an alcove off the kitchen with a commercial-size gas range with multiple burners and ovens and a high back, and I can picture her standing in there, dwarfed by that huge appliance. The most amazing meals emerged from that small corner. And her desserts! Pineapple-cheese pie, meringues with fresh strawberries, lemon cookies, and apple strudel, her specialty.

If Sophie was the chef extraordinaire, Hans was the manager extraordinaire. He kept the place humming. He walked fast, talked fast, and seemed to be everywhere all at once. He and Sophie were a team, and it was his job to see that she had everything she needed. I remember them conferring about the menus before he would make a run to the Wholesale Block in Scranton. Hans was a stickler about his knives—no one was allowed to touch them. So, of course, Sandy would move one just to tease him. He’d go along with it and yell, “Who touched my knives?”

Waitress or not, we all pitched in with the meal preparations, peeling what seemed like a bushel of potatoes every day, Frenching string beans, grating potatoes for potato pancakes, peeling apples for strudel.

Lunch was at noon and dinner at 6:00, and both were served family style. I remember roast beef or lamb, stuffed or breaded veal, corned beef and, once in a while, chicken. They didn’t serve ham or pork, menu mainstays at other farm-boardinghouses. On Sunday the main meal was served at mid-day, and supper was light with a sampling of breads and fresh fruits, sour cream and cottage cheese.

Guests were seated at long tables in the dining room, and if there was an unexpected overflow on a busy weekend we set up extra tables on the enclosed side porch. Mealtimes were lively, sociable occasions, and the guests tended to linger over coffee and dessert. It could be a quite a chore to sweep them out of the dining room so we could set up for the next meal.

After everyone was served, we gathered around the big oak table in the center of the kitchen for our own meal. Unlike the guests, we didn’t linger—there were dishes to be done. Every dish, every pot and pan, every utensil was washed and rinsed in the big double sink and dried by hand and put away. We didn’t finish up until 8:00 or 9:00 at night, long after Hans and Sophie had retired to their room off the kitchen.

Another task that fell to us girls was the laundry. There was a wash house out back with a wringer washing machine but no dryer—everything was hung out on the clothesline to dry. The bed linens and tablecloths had to be ironed before being folded and put away, and this is when I encountered a huge apparatus called a mangle iron. This machine was my nemesis. It had a wide padded roller that heated up (it heated up the wash house too), and you fed the folded linens into the hot roller and they came out the other side flat and crisp. Hilda preferred the wash house to the kitchen, and I preferred the busy kitchen, so fortunately I didn’t have to mangle sheets too often.

They were long days with only a short break in the afternoon, but we had time for fun, too. I turned 16 that summer and to celebrate, Sandy and her friends took me to The Old Ranger’s Inn for a night of square dancing. At Fairtime, I walked down to the Fair with Rachel and Peter Kline, whose family had been regular guests for years—a three-mile hike but none of us had a car. We went on rides, shared cotton candy and tried to win a goldfish. At one of the booths, a man had to guess a person’s age within a year or you would win a prize. Rachel was 17 and Peter was 14 and tall for his age. When the man guessed 16 for Peter, we all cheered.

That was Hilda and Sandy’s last summer at Panther Lodge. The next summer Janice Smith and I were the full-time waitresses. As I look back on those summers, I realize that working at nearby hotels and boardinghouses was a rite of passage for us young teens. The owners were our friends and neighbors, and they were willing to mentor us and help us learn the skills we needed to do our jobs. Along the way, we also learned how to work hard, work fast, and work as a team.

For the story of our local boardinghouses, go to the “Farmhouse to Boardinghouse” presentation by Bernadine Lennon on the GDHS Channel on YouTube.