In the early 1800s, people left their homelands in Europe and emigrated to America for a variety of reasons, and chiefly among them was religious persecution. Hopedale Church history records that the families who settled in Newfoundland around 1829 came from Gondelsheim in the Grand Duchy of Baden, Germany. The prince who ruled Baden at the time was Lutheran, and therefore the Lutheran Church was the state’s official religion. While living in Gondelsheim the families were receiving religious services from itinerant preachers of an Evangelical Association, and because the Lutheran Church was opposed to this practice, they were subject to arrests and fines by the local authorities. In the families’ own words “their local pastor was their worst persecutor.”

In 1828, fifteen families emigrated from Gondelsheim, Germany, and many of their names are still familiar today— Able, Beehler, Beehn, Friebele, Hech (or Eck), Heffeley, Schneider, Krause, Raetz, Waltz and Wolfe. Four of the families traveled together on the Bayard, a three-masted sailing ship which left the port of Le Havre, France, in July 1828 and arrived in New York on September 5, 1828. The occupations of the passengers on the Bayard included farmers, millers, and weavers, and their ages ranged from 1 month to 46 years. The ship’s captain recorded that no deaths occurred during the voyage, which was remarkable for the time.

The Newfoundland Settlement

Once the German families arrived in New York, they traveled on foot to the Lehigh Valley where they stayed for a time, perhaps as long as a year, with other German families in the Moravian communities of Nazareth and Bethlehem. The Moravian Church was already well-established in eastern Pennsylvania, and Bethlehem was a thriving city.

How did the new immigrants hear of land for sale in the Wallenpaupack Valley? There was a lot of land speculation along Pennsylvania’s northern frontier in the early 1800s, but very few, if any, of the investors resided on the land they owned. Abraham Singer, a prominent businessman in Philadelphia, had purchased a tract totaling 2255 acres that encompassed the Newfoundland Settlement. He began selling parcels as early as 1812, when he sold 54 acres to William and Mary (Coe) Akers and 100 acres to Akers’s son-in-law Gabriel Davies.

In 1824 three generations of the Rohrbacker family—Christof and Elizabeth and their six children, including their eldest son Jacob and his wife Christiana and their two little sons—settled on land adjacent to the Akers farm, near the confluence of Wallenpaupack and Mill Creeks. Christof and his sons built a gristmill along Mill Creek, and the Rohrbacker family was influential in the early development of the area. Since they had also lived in Baden before emigrating to America, it is possible that they knew some of the German families and remained in contact with them. They may have informed the families who came later that there was land available in the Newfoundland Settlement.

In November 1829, Jacob Rohrbacker and David Wolfe, who had sailed on the Bayard, entered into a business partnership to purchase approximately 2100 acres, the same tract that encompassed the Newfoundland Settlement, from Abraham Singer’s daughter and heir, Maria Shively, of Philadelphia. Rohrbacker and Wolfe were acting on behalf of the German families, who had already left Bethlehem and were homesteading on the land. Maria Shively held the mortgage of $4400 on the 2100-acre tract of land. The conditions of sale were that the first payment of $1100 was to be made in 1831, with payment of $1100, plus interest, on alternate years until final payment in 1837.

The 1830 Federal Census lists 13 German families living in the Newfoundland Settlement. Additionally, the Hopedale Church register records that the first birth in the settlement was Charles Louis Heffeley, born on December 19, 1830. These two pieces of information support the fact that the German families were living on the land before they were deeded their individual lots in 1831. This is quite remarkable given that they had arrived in America in the fall of 1828 and in less than two years had found land, built suitable structures to live in, and found adequate food sources to see them through the harsh winters.

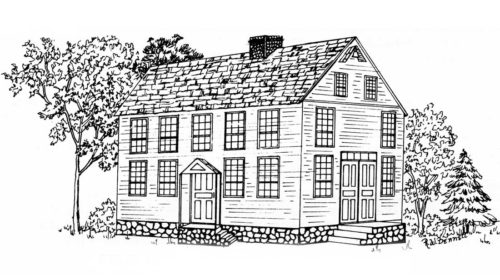

When the German families arrived here, the area was sparsely settled. Roads were primitive, and there were no schools or churches that typically make up a community. What the settlers had were the natural resources of the valley—fertile flat land on which to grow the crops so important for their survival, and timber to build and heat their homes. Their first dwellings might have been log houses or, since there were sawmills nearby, plank houses ranging from 16’ wide and 24’ long to roughly double that size. They were probably one and a half or two stories with a center chimney, six-over-six pane windows and eyebrow windows on the second floor, and a wood-shingled roof.

Rohrbacker and Wolfe had the land surveyed and divided into 30 narrow lots, each about one mile long and 200 to 400 feet wide, and averaging between 25 and 50 acres. The lots crossed the Newfoundland Road and extended across the fertile valley and up the forested hills on either side of the creek. Because of this configuration, each farm included a portion of the rich bottomland along the creek, as well as ample supplies of water and wood. However, the immigrant families could not afford to buy their own lots. When they tried to borrow money from banks in Easton and New York, they were turned away because the land had little value and the families were so “bitterly poor.” The 1912 Hopedale Church history states that a Moravian minister intervened on their behalf, and through his efforts, the Moravians of Bethlehem extended loans to those who needed them. Most families purchased two lots, but in many cases, their lots were not contiguous. The lots being narrow, the houses were built close together, making it easier for the families to help each other and worship together.

Moravian Church Mission

At first the settlers held worship services in their homes, as they had in Germany. Being a missionary sect, the Moravian Congregation at Bethlehem sent pastors into the outlying areas to preach in the homes of settlers, and they often visited Newfoundland. In 1835, the Bethlehem Congregation purchased a 50-acre lot in the center of the settlement for a “church farm.” A church was erected on part of the land, and the remaining acreage was reserved for a farm to support the minister and his family. Of simple design and solid wood construction, the building measured 35 × 40 feet and was two stories high with a large meeting hall, or Saal, on the first floor for worship services and smaller rooms on the second floor for the minister’s family. The 5-bay, center hall style was typical of homes in the area, and you can often see this design in local farmhouses. The number of windows was notable, since glass would have been a luxury at the time. Although at first the church had no organ or melodeon, one pastor wrote “almost all the Germans are musical and we frequently hold Singstunde, or singing meetings.” At night the room was lighted by tallow candles in a wooden chandelier. Sometimes during evening services the candles would sputter out and the people would have to return home.

The first resident pastor arrived with his wife and four children in August 1837 and moved into the parsonage upstairs. He held a special service to dedicate the new church and welcome the Congregation. Afterwards a “Love-Feast” was held outdoors for the entire community, and women baked special breads and cakes for the celebration in an outdoor brick oven that had been built near the church. The Congregation chose Hoffenthal as the name for their church, which means Valley of Hope, or Hopedale, and reflects the spirit of those who left the Old World for the New in hopes of a better life.

The pastors assigned to the Hopedale Congregation were experienced missionaries. Prior to serving at Hopedale they might have been appointed to missions in Alaska, Canada, the West Indies, or the American Indian territories of the West. There are no diaries to tell us what life was like for the German settlers, but the letters written by the pastors to their bishop in Bethlehem reveal some of the joys and hardships of life in the Beechwoods, as the region was called.

They picked us up with ochsen [oxen] and a sled, which I found very interesting. I was impressed how these animals understood the words of the driver, and he commands them without a bit or rein. So far we have not felt any hardship and there is no shortage of rye or buckwheat. We have provisions of this and pork, sausage, and vegetables, which were brought here. If I might get a pay in money I am not sure, and I did not ask if anything is forthcoming. I know that there is little of it. —Pastor Peter Ricksecker, 1850

During the early years the settlers endured epidemics, floods, crop failures, harsh winters, internal conflicts, and poverty. The pastors cite illnesses such as, typhoid fever, colds, pain associated with poor teeth, quinsy, which is a complication of tonsillitis, whooping cough, mumps, erysipelas (streptococcus infection of the skin) and yellow fever. A letter written in June 1850 notes that the pastor and his family suffered from recurrent colds because for a few months water was constantly in the basement of the parsonage, sometimes as much as three feet deep. In 1851, the pastor described the settlement, saying, “While it is true that the first settlers had a most trying time and often had to go to bed hungry, it is a most healthy part of the country which is well watered, has a good market for every produce, the land is cheap, and people can live cheaply.”

To give you an idea of the size of the congregation, in 1842 the church record book listed 107 individuals who had formally joined the church: 26 married couples, 1 single man, 1 widow, and 53 children. Among the new members were the Heberling, Kindt, Schall, Waltz, Schaeffer and Wesserer families. In addition, there were several persons who had not formally joined but were served nonetheless. Meetings were well-attended; however, members had little cash. In 1848 Pastor Simon reported that the total collection for the year amounted to ten dollars, three dollars in cash and the rest in working on the church-farm. He wrote, “I have sacrificed the best part of our money intended for our old days, and have not sold $50 worth of product raised on this place in five years. I am in want of clothing since I have been here.”

Farming

The pastors and their families maintained the church-farm, with help from members of the congregation when they could spare the time. They planted crops and raised animals, and what they didn’t need for their own use they sold for cash to help support themselves and the church. Their letters often mention the harvest. The Newfoundland Road had been upgraded to a “turnpike” in the 1840s and it connected the settlement with Honesdale, Stroudsburg and Bethlehem. The pastors helped forge economic links with these centers of commerce, and the settlers found ready markets in these cities for their vegetables, grain and lumber.

The families struggled to produce enough food for themselves and also make a profit. Most farms had two or three milk cows, a couple of hogs, some sheep and chickens, and a pair of oxen, which were used for farm work. It was rare to find a horse prior to 1870. In 1850 the entire potato crop failed, which was a considerable loss. In addition to potatoes, the farmers planted corn, hay, oats, rye, and buckwheat.

Formerly, they had not worked as farmers, but now there are several who do and they grow all kind of produce and vegetables that can be sold. It should be considered, that most of the settlers are tradesmen and never will make real good American farmers, yet most of them are doing pretty well. I wish some real good farmers would settle here and by their example, teach others how to farm.

—Pastor Peter Ricksecker, 1851

In 1854 the pastor sketched a diagram of the church-farm, which included the church, parsonage and school, and made notations in both English and German describing the land. At the center of the farm were 30 acres of good, rich land, some of it wetland which can be made use of by digging ditches. On the east side, bordering the creek, there are two fields where most of the stones have been taken away and land can be plowed. As the land starts to climb on the far side of the creek, he states that it is bad land, partially unusable, with bushes. On the west side, across the road, he indicates woodland and grassland and writes, “the strip along the creek [a small tributary] is good, the rest is torn up by storms. Many lambs die off.” This description probably fits most if not all of the other farms in the settlement.

A New Church and Religious Conflict

In 1850, the Hopedale Congregation had grown to 173 members, and again, half of them were children. At the urging of the pastor, the Bethlehem Congregation agreed to replace the old meeting house with a larger “well-appointed” church and separate parsonage. When construction began in June 1852, sixty-six men, all members of the Hopedale Congregation, were on hand to break stones and lay the foundation. The new church, in the Greek Revival style, was not quite as elaborate as the original plan, but a new pipe organ was placed in the choir loft and a “real bell” hung in the turret, a gift from the children of the congregation.

Pastor Oehler served the Hopedale Congregation from 1854 to 1856, and his letters show that there was discontent among members during his tenure. One man wrote that Pastor Oehler was hard to be around and that because of him he was withdrawing from the congregation. Several other families left the congregation to form the Albright Evangelical Church. Jacob Rohrbacker and his family moved to Douglass County, Kansas, and at least four other families traveled to Minnesota, where they established new Moravian Congregations in the wilderness of Carver County.

However, disunity in the Hopedale Congregation and in the community was not the norm, and many letters are witness to that fact. Moravian Churches were built in Canadensis (then known as Coveville), German Valley, and Roemerville, and all were part of the Hopedale Charge. As we have learned from their letters, the pastors were generally leaders in welcoming new churches into the community and fostering an ecumenical approach toward worship.

Yesterday morning I walked nearly three miles to a Catholic family. The mother of the house I was to bury. It was an important time to me. I felt confident that all the Catholics near and far would be present. I preached to a full house and made an effort to undo denominational bigotry. —Pastor Detterer, January 1866

In December 1873, another pastor wrote: “Christmas day brought us another glorious spiritual feast. Our services were once more of a union kind. Methodist Episcopals and Moravians and Catholics worshipped together in the little Church. The Methodist Episcopal pastor preached in the English language and I attended chiefly to the German part of these services. People looked upon this union worship as replete with encouragement and reinvigoration. The church was nearly filled and we could not have desired better decorum and attention.”

An 1895 daily calendar notes that each month Pastor Wantzel visited more than a dozen homes of both members and non-members.

Influence of the Moravian Pastors in the Settlement

The pastors were in many ways community leaders. For many years, Newfoundland was an enclave for the German families where German was spoken and the immigrants held to their culture. The village was often referred to as “Dutch Flats,” from the word Deutsch, meaning German. The pastors conducted services in both German and English and helped ease the transition to English literacy for the families, especially the children. In 1850 the pastor requested that the Bethlehem Congregation replace the German songbooks with English. The transition to English took a decade or two, and even into the early 1900s German was spoken in some homes.

In addition to their spiritual duties, the pastors offered practical guidance that played a vital role in the success of the early settlement. They acted as mediators between the German-speaking families and neighboring English families and local government officials. This was an advantage for people who were applying for citizenship, entering into contracts, paying taxes, and things of that nature.

My position here is becoming more important, so that I begin to be anxious that I am doing too much. I am consulted concerning the sale of land and the buying of land. In the 24 hours before I began to write this letter, I had made and concluded a written agreement for a man in Hawley who is moving here to keep a store. —Pastor Gottlieb Oehler, 1855

Because the Moravians placed such a high value on education, the pastors were leaders in promoting education in the settlement. They were the first schoolteachers for the children of the community, organizing a Sunday school as soon as the church was built, and then in 1841 taking charge of the “free school” with 30 scholars, who he instructed in the parsonage. The first common school for grades one through eight was built on church land and called Hopedale School. It served children from both Greene and Dreher Townships, a tradition that continued through the years as each school was replaced by a newer, larger building.

The early pastors operated an informal post office, receiving and distributing mail to members of the congregation, and probably the wider community as well. A mail wagon made a weekly circuit on Fridays and passed through the settlement on its way from Sterling to Stroudsburg, Easton and Bethlehem. The wagon, later the “postal coach,” also transported passengers between Hopedale and Bethlehem. When a post office was officially established in the village in 1855, the pastor and his wife served for a short time as the first postmasters.

And lastly, the pastors were advocates for support from the Bethlehem Congregation, requesting food, clothing, medicine and financial support for the congregation whenever needed. And they contributed financial help themselves. In 1849 Pastor Simon wrote that he had collected $10 from the congregation the previous year, an amount that fell far short of expenses. He drew upon his annual stipend to fill the gap.

Summary

When the settlers divided their land into long, narrow strips that crossed the Wallenpaupack Creek, their properties also crossed the political boundary that separated not only the townships of Greene and Dreher, but also the counties of Pike and Wayne. This meant that landowners had to conduct business and pay taxes in two relatively distant county seats, Honesdale and Milford, located in opposite directions. It also typically meant two separate school districts, but when a high school was built in Newfoundland in 1901, it became the first school district in Pennsylvania to cross a county line. From the beginning, the community functioned as a single unit. This was due in part to the cohesiveness of that first group of settlers and their descendants, many of whom still live in the area, and to the influence of the Moravian pastors who guided their flock through the first few decades.