by Diane Smith

A Granddaughter Remembers

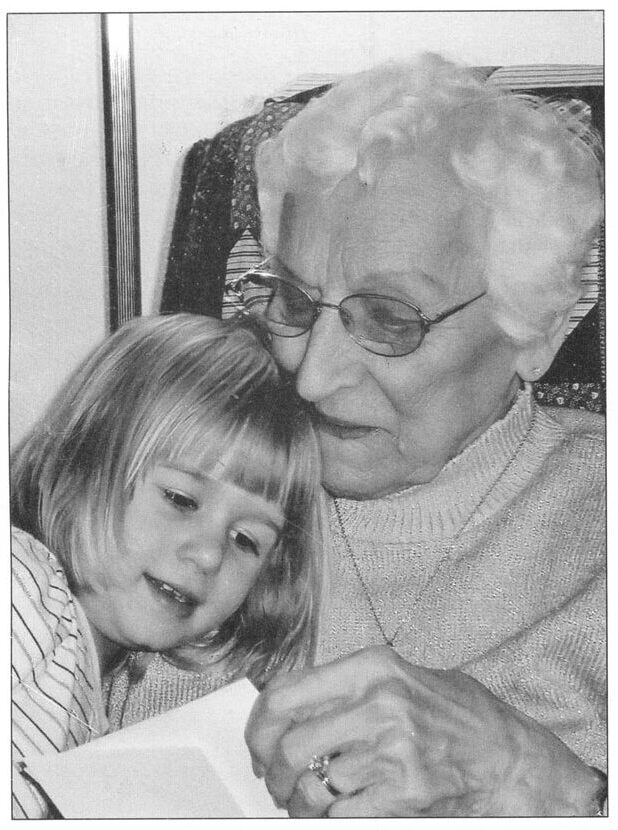

My grandmother instilled in me a love of nature. When I was very young, she took me out walking in the woods and fields surrounding her house, teaching me every different tree and flower, studying the leaves, bark and petals to distinguish one from the other. I am now attempting to teach my daughter, Molly, just like Gram taught me. We hunted for arrowheads, one of Gram’s favorite pastimes. She had a substantial collection. The other day I opened a not-often-used cabinet to clean it, and what did I find lying at the bottom? An arrowhead! She is still leaving me “gifts,” even after her passing. We are so blessed to live in Gram’s house. Its attics, drawers, and cupboards still hold treasures from long ago, which we are slowly uncovering—postcards, diaries, photographs, and records of the lives and times of the people who lived here. Gram believed that the history of this area is important. Now she is a part of it, too.

—Julie Hazelton Dickerman, 2009

Anna’s Family

Anna Louise Haag was born on the family homestead in 1911, the daughter of John Adam Haag and Agnes Rohrbacker. Anna’s ancestors were among the first to settle in the Wallenpaupack Valley in the early and mid-1800s, having left Germany for the promise of religious freedom, land ownership and business opportunities in the New World. Both of Anna’s first-generation grandparents were mill owners—the Rohrbacker and Haag gristmills operated along Mill Creek in South Sterling in the 1800s and into the first decade of the 1900s.

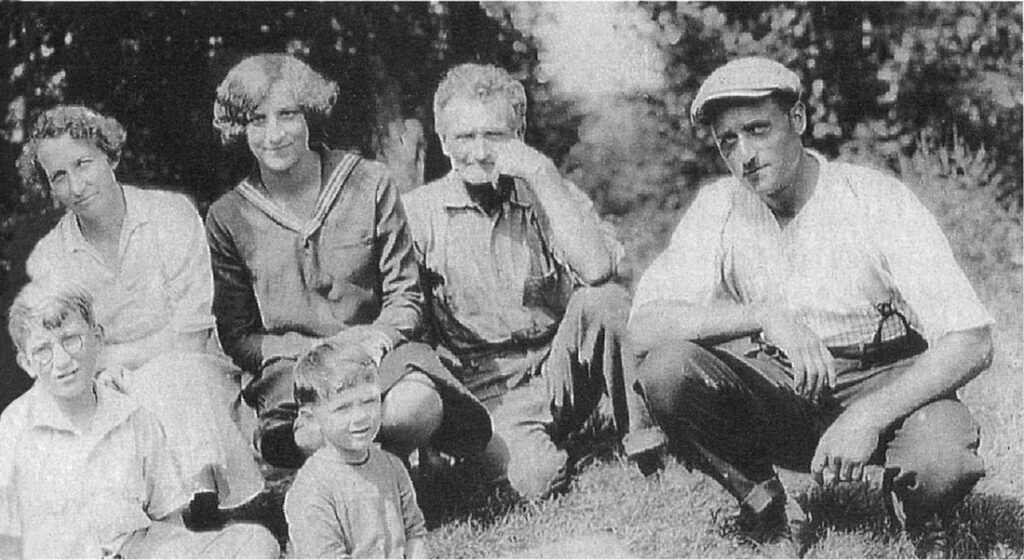

When Anna’s parents married in 1907 the young couple resided with John’s father, William Haag, a widower, on his farm in Greene Township. Anna was the second eldest of their five children, one of whom died as a young child. Anna and her younger sister, Ruth, only a year apart in age, were the closest of companions growing up on the family farm. The Haag children attended Sugar Cabin School, the same one-room school their father had attended, and all but Anna went on to graduate from Greene-Dreher High School.

The Farm at the Top of the Hill

Located at the top of Brink Hill, the Haag farm consisted primarily of forestland—maple, cherry and beech, with swaths of hemlock and pine in the low-lying areas—and swampland fed by a small stream that flowed from natural springs and an artesian well below the barn, and about 30 acres of cleared land for crops and pasturage. The farm fields were lined with stone walls, still standing after nearly 200 years. The big field above the house commanded a view over the treetops to the Moosic Mountains far to the west.

The farmhouse was an unadorned timber-frame structure that had been added onto and reconfigured over the decades. When Anna was a child, the house was one room deep with three rooms down—living room, dining room, and kitchen—and four rooms up, accessed by a steep, narrow enclosed stairway between the dining and living rooms. An east-facing porch with two entrances ran the width across the front of the house. The kitchen door was used every day by family on their way to the barn and to do chores, and the door to the living room was used on Sundays and when company came calling.

The kitchen was fitted with a Hoosier cupboard, a dry sink lined with zinc with doors underneath, and a massive cast-iron, wood-burning cook stove that all but filled the room. It had a six-burner cook top with a narrow warming shelf above, oven door, side grate door, an ash shaker and ornate nickel-plating on the legs and trimmings that glowed softly in the kerosene light. Electricity wouldn’t arrive in the Haag household until 1927, and as long as John and Agnes lived there, the house did not have running water.

The plaster walls in the dining room were painted a vivid blue with a dark red chair rail. Interior doors and trim were finished with painted wood graining, a style that was popular in the 1800s to make softwoods like pine and hemlock look like more expensive wood, in this case, oak. The living room was well-lighted by four windows. Agnes placed her platform rocker next to the west window and this is where she did her mending, quilting and sewing. A piano stood in the corner with German sheet music in the rack. The room was heated by a potbelly stove, and in the evenings John liked to sit on the straight-backed chair next to the stove and smoke his pipe.

The bank barn next to the house had thick fieldstone walls on three sides with earth banked halfway up. Two small window openings about 20 inches in height admitted natural light in the stable on the lower level. The stable doors opened to a small farmyard bordered by a low stone wall. A raised earthen bridge provided access to the threshing floor and hay mows on the upper level. The 1927 Farm Census reveals a small farm—one milk cow, one heifer, 10 acres planted in hay, two horses, two pigs, 25 chickens and an apple orchard—sufficient for the family’s needs, supplemented by hunting, trapping, fishing, vegetable gardening, berry-picking and bee-keeping. Around 1930 John built a wooden silo on the east side of the barn and expanded the dairy herd to eight milk cows.

In addition to farming, John Haag held various jobs over the years. One of his first jobs was installing telephones and repairing lines for the Wynoosky Telephone Co., a local company established in 1899 by a group of enterprising businessmen; William Haag was a shareholder. John was a sales agent for McCormick-Deering for forty years, representing the line of tractors and farm machinery manufactured by the International Harvester Co. Their products included Farmall tractors and household appliances, such as washing machines that could be powered by a gasoline engine, electricity or a line-shaft drive. In winter when business was slow, John cut ice on local lakes and ponds and did some lumbering on his own property. When Route 390 was under construction in the early 1940s John was “stone boss,” supervising a crew of men who broke up rocks with sledge hammers to form the crushed stone base for the road. The men were paid ten cents an hour for this labor-intensive work. For most of his life John worked part-time as a grave digger for several local cemetery associations, using a pick and shovel and blasting with dynamite when necessary.

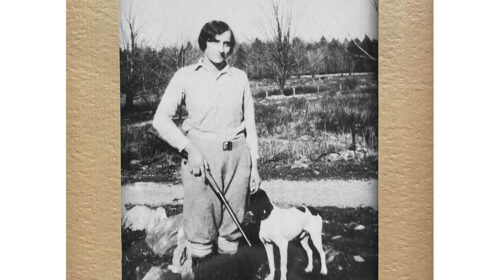

John Haag was a renowned hunter, naturalist and outdoorsman. He knew the woods like the back of his hand and served as a Pennsylvania Forest Fire Warden for 35 years, retiring in 1966. A sideline to his hunting prowess was taxidermy. He had animals and birds preserved and mounted and sold them to local families and vacationers. A few prime examples were displayed in the Haag home, including a bobcat, fox and great blue heron. Anna’s favorite was the great horned owl.

At the age of 90, Anna Haag Hazelton London recalled her early years on the farm. Her oral history was published in The Greene Hills of Home in 2002, and the article is included here:

My Early Years

by Anna Haag London

We lived on a little hill just off of Blooming Grove Road. My older brother Don and my younger sister, Ruth, and I went to Sugar Cabin School. We walked about half a mile from our house up over the hill and through the woods to the schoolhouse. We followed the same path that my father took when he went to school there. In the winter the snow would be up to our knees, so we wore leggings made of heavy black material with fleece lining and a little shank on them. They buttoned all the way up, and somewhere I still have a string of those buttons. In deep snow, Don would walk ahead of Ruth and me to break a path for us. We always carried our lunch pails. One day our teacher, Miss Sieg, looked out the window and saw a bear coming across the field. She let us all jump up and look out the window—we were very excited. There were very few bears at that time, and hardly any deer.

We had six or eight cows on the farm. I knew how to milk them, but I hardly ever did. Every fall after the crops were in and the grass was still green, Ruth and I would have to chase the cows out of the pasture and into the green meadow. We’d do that every afternoon after school and watch them so they wouldn’t get into the road or into our neighbor’s field. In the fall, when the well along the road went dry, we had to chase them down to the woods to an old well to drink. While we watched them, we would play in mud puddles and build little dams with stones. Once I found a soft stone. I always carried a pocket knife, so I whittled 1924 in that stone. I still have it somewhere. I also whittled out of wood a little cage with a ball inside it. When it got dark, we would bring the cows home and put them in the barn.

In the mornings we’d have to haul water in for Mother. We had to carry wood in too, if Daddy was out selling McCormick Harvester equipment. That was hard work.

There was a white pine tree that stood almost alone in my grandfather’s pasture…alone because it was so much taller, so much larger, so much older than all of the other trees. When we were children, we were never allowed to play around the tree because we had two horses in the pasture, Daisy and Dan. Daisy had a disposition that wasn’t at all nice and would chase anyone who entered, while Dan was gentle. He would lie down on one side and couldn’t get up until someone would roll him over. I am sure he appreciated the help.

When World War I started, everyone was poor. Food was scarce, and you couldn’t get sugar. We used to tap maple trees in the spring and boil the sap until it turned to syrup, and then we boiled it some more until it turned to sugar. We had all of our homegrown vegetables, apples, and pears in our cellar. My mother’s canned goods were stored on shelves made of boards laid across layers of stones. Potatoes and apples were in bins, and they lasted all winter. Those russet apples were so good! I’d eat five or six of them at night before I went to bed. We raised our own beef, pork, and chickens, and Mother made corn meal mush and corn bread. We never went hungry.

At Christmastime Mother would take us out to pick princess pine. She would put a sheet up in a corner of our living room, and we would pin the sprigs of princess pine on it. Dad would cut a tree from our woods and put it up in the living room. We would put paper down under the tree and collect different kinds of moss and lay it on the paper and make little villages with paper houses, sheep and other animals, and sawdust for the roads. That was fun! Our parents would decorate the tree after we had gone to bed on Christmas Eve. Mother had those pincher holders for candles, and on Christmas we would light the candles on the tree and sit around and watch them flicker and burn. During World War I at Christmas, we hung our stockings up and got homemade cookies, candy, and an orange at the bottom. I was so happy when I got a pair of buckled arctics (boots). All of the kids got arctics. They were fleece lined. I thought that was the nicest present I ever got. Guess I have always had cold feet.

Winter is the best time of all. The birds have left, the animals are denned, the lake is quiet, and then a new way of life starts. Ice skating! Young and old come out for some real fun—Dick Simons, Audrey Ramble, Dick and Max Hazelton, Anna and Ruth Haag, Jack Walter, Charles and Dave Walter, Bob Krieger, his dad, Dorothea Krieger, Marion and Edna Fowler, Esther, Gertrude and Jeanne Grimm, Al “Red” Smith, Victor Butler, the Hasers, Earl Price, Doc Rile and perhaps some Sheerers. Your skates had to be very sharp as the ice was so slick. The younger ones skated earlier in the day, and they would build a fire to keep warm. The evenings belonged to the older ones. They baked potatoes and made other goodies. Some skaters came in their sleighs and some walked, but however they got there it was great fun!

—Miriam Sheerer, 1993

When we were little, Ruth and I would find a dead bird once in a while. We would dig a hole, bury the bird, and make a fence out of sticks that we stuck in the ground. We’d put a piece of cord around each stick for a little fence around the grave and find a stone to stand up for a marker. Then we would sing some songs to the bird, probably “When the Roll is Called Up Yonder” and “Bringing In The Sheaves.” For one broken doll for which there was no help, Ruth and I put her in a shoe box and dug a hole halfway between the road and our house and marked the grave with a large stone. We sang, and Ruth probably cried because she liked dolls better than I did. Ruth and I would bury only birds and dolls, no cats or dogs. Dad would do that.

When I was about twelve, my father taught me how to set and bait a trap. I would set box traps and bait them with apples to catch rabbits. My dad would skin the rabbits and take them up to the house for supper the next day. We also ate squirrels, raccoons, and woodchucks. After the woodchucks had been out of hibernation for a month, they were good eating.

In the morning, before the snow fell heavy, I would go out to check the traps. One time I got my neighbor’s cat! Arthur Reeves wasn’t too happy about that, but fortunately the spring trap didn’t break his foot. The next time I got a skunk, and my dad had to kill it. That ended my trapping, but I did learn that the more black fur there was on a skunk, the higher the price was for the hide. My brother Don was never interested in hunting or trapping, even though at that time almost everybody trapped. I still have a couple of those old traps hanging in my garage.

Almost every farmhouse on Brink Hill had extra rooms and would keep boarders for the summer. People would come from the city for their vacations and to enjoy country living. They would come by train to Cresco where they would be met with horses and wagons, and later by car, and taken to a boardinghouse. When boarders were staying with neighbors, they would take walks past our house. Sometimes Ruth and Don and I would sit down by the road and meet these guests and talk for a while. They would give us peppermint candies and tell us a little about city life, how they rode on street cars to get around.

I remember one time when Don and I saw a strange looking man coming down the road carrying a box and leading a monkey on a string. My grandfather gave the man a few coins, and the monkey turned the handle on the box and played music. Then they went on. One other time someone came along with a young brown bear on a rope. He didn’t stop at our place, but he did stop in Greentown where the bear got loose and climbed up a telephone pole. The bear must have been comfortable up there because it was a couple of hours before he came down. I guess some people did things like that for a living.

Every summer there would be a caravan of Gypsies come through past our home. Mother would hear the sound of the horses and the rattle of the wagons coming down the road. I think Blooming Grove Road was a shortcut from New England to get down south where it would be warmer for the winter. It was fun to watch them in their colorful clothes as they passed by. The last time I remember them coming through they came in old cars. It must have been around 1930.

When I was about twelve, I was my granddad’s pet. Every week I would shave him with a straight razor for ten cents. I must have spent all my money because when the church had its picnic I didn’t have any money left and there were lots of good things to buy. They had this ring bologna hanging up that I liked, and I bought four inches of it. They had bananas and candy, too. So, I borrowed thirty-five cents from my sister, and paying it back was the hardest thing I had to do. I learned my lesson. I have never borrowed any money since. No matter how much I wanted something, I would wait until I could pay cash for it.

Anna Haag married S. Richard Hazelton in 1932, the height of the Great Depression. Dick and Anna took over ownership and management of the S. R. Hazelton General Store in Greentown, established in the 1800s by Dick’s parents. Located at the village crossroads, the store offered various and sundry goods, from household and farm items, to clothing and grocery staples. It also included a car dealership, established by Dick’s father around 1910, and they sold Ford, Durant, Star Car, Dodge, and Plymouth. An automotive repair garage was located in back, and there were three gasoline pumps out front. Anna remembered pumping gas by hand, “You had to go round and round to pump that gas.” The Greentown Post Office was moved to the rear corner of the store, and Dick served as postmaster for the next 18 years. The family residence was adjacent to the store, and that’s where Anna’s three children were born. Their daughter Elaine recalls that her mother would prepare holiday meals for the older men who would spend their afternoons sitting on the porch in front of the store, or gathered around the wood stove on cold winter days, visiting with customers and each other. “She had the first ‘Meals on Wheels,’ delivering holiday dinners to their homes.”

Anna enjoyed working in the store and helping out in the post office. One summer an artist rented the apartment on the second and third floors above the store, and he worked in exchange for food. He taught Anna the delicate art of wood graining, a technique that requires an understanding of nature as well as a steady hand. She acquired the necessary tools and decorated several pieces of furniture for their home. A large oak cabinet with burled panels held a place of honor in her parents’ dining room and remains in the family. Anna also learned oil painting, a hobby she enjoyed for the remainder of her life. She often depicted flowers and familiar landscapes, and her paintings won several ribbons at the Greene-Dreher-Sterling Fair.

When Dick and Anna retired from the mercantile business in 1950, they sold the store and bought a home on Brink Hill, not far from where Anna grew up. It had been the summer home for a family from Philadelphia. Dick went into dairy farming with a herd of 20 to 30 Holsteins. At first he rented the barn and surrounding fields on the adjacent Ramble farm, no longer in operation, until he built a new barn with all the modern conveniences—milking parlor, ample lighting and ventilation, running water, mechanical milking, detached milk house, and as fireproof as a barn could be. There was some excitement on Hazelton farm when triplet calves were born and neighboring families stopped by to marvel at their rarity and healthy rambunctiousness. In addition to farming, Dick also drove the school bus, ferrying pupils back and forth along the Brink Hill-Greentown-Hemlock Grove route each day. One of his first riders was his future wife, and when he retired 45 years later he could count among his passengers his three children and at least one grandchild.

Anna’s sister Ruth recalled her keen eye in finding arrowheads and four-leaf clovers. While in their 80s, the sisters made their way down the Grand Canyon on donkeys. Anna was known in the family for her marksmanship, having been taught those skills from the age of ten by their father. One time she fashioned a rifle rest out a branch and picked off a 5-foot black snake that had taken up residence inside a birdhouse. Another time a skunk had gotten its head stuck in a Mason jar, and she handled the problem by shattering the jar with a .22 bullet, freeing the startled skunk.

Anna took up oil painting in her later years and often depicted flowers and familiar landscapes, for which she won several ribbons at the Greene-Dreher-Sterling Fair. She enjoyed gardening, cooking and baking, and was known for her strawberry shortcake. She gave up shooting and hunting in favor of wilderness conservation and was an active member of Lacawac Sanctuary in Ledgedale. She was a lifelong member of the Hemlock Grove United Methodist Church, a 50-year member of The Eastern Star, a member of the Newfoundland Woman’s Club, and a founding member of the Greene-Dreher Historical Society. Only nine when the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, Anna never once missed voting in an election.

S. Richard Hazelton died in 1968 and Anna remarried, first to Oscar Schoenagel and after he died, to Neal London. Anna passed away in 2009 at the age of 98. She is remembered as a kind-hearted, hardworking and generous woman. She loved her family, and she loved the outdoors.