by L. Webster Gilpin Jr.

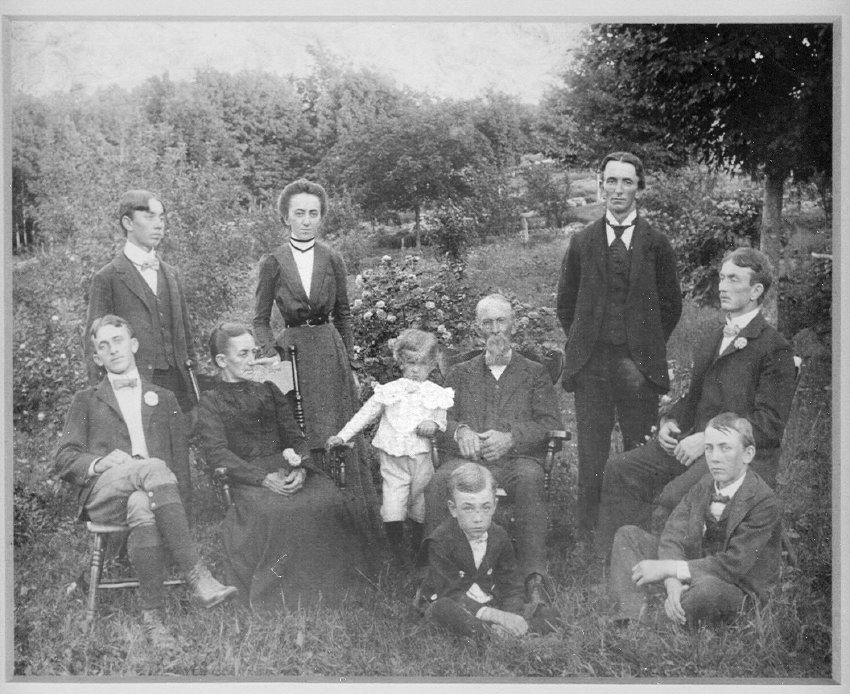

My family has been here a long time. My great-grandparents Jefferson Webster and Clara Hause bought a 50-acre farm in Angels around 1880 and settled there with their four children, the youngest of whom was four-year-old William, the future Forest Fire Warden at Gould’s Tower. Four more children were born on the farm. In addition to tilling the land, J.W. worked as a butter maker at the Newfoundland Creamery. Aided by his young “helpers,” he would make a half ton of fresh butter every day and haul it to the large boardinghouses and hotels in Mt. Pocono, about 20 miles away. After J.W.’s death in 1920, Clara sold the farm to their son Raymond and daughter Mary, known as Mamie, who had married Maurice Gilpin in 1913. William and his wife Frieda lived on the adjoining farm where they operated a summer boardinghouse called Echo Inn.

The Pennsylvania Forest Commission approached Mamie and Raymond in 1921 for permission to build a lighted tower at the top of Hause Hill as a beacon for planes. Up to that time very little night flying had been done and there were no lighted airways in existence. The U.S. Army Air Service had carried out some experiments and developed certain necessary equipment but had attempted very little cross-country night flying. It was the Post Office Department that led the effort to implement night flying, assisted by manufacturers of illuminating equipment of various kinds—landing lights for planes, lights to mark fields and terminals, beacon lights for mountaintops en route. They established the first transcontinental airmail service between New York and San Francisco in August 1923.

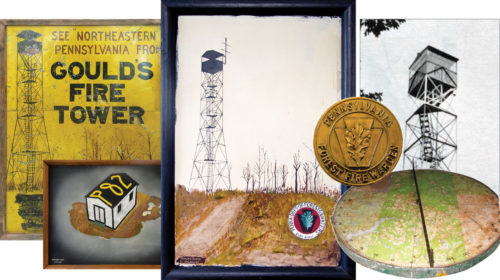

A small wooden tower was built on Hause Hill that would be lighted to guide planes flying between New York and Chicago; however, it was never commissioned. It would have directed planes over Picatinny Arsenal and, given the unreliability of night flying at the time, they changed the route. The tower was torn down almost as quickly as it was put up. Instead, a fire tower was built on the same site in April 1922. Mamie and Raymond allowed the state to erect a a 75-foot tower for the purpose of detecting forest fires for hundreds of miles. It was named after J. Gould, whose immense fortune had its beginnings in the tannery industry and whose enterprises extended into Wayne County. One of his tanneries stood on the Lehigh River at the present site of Gouldsboro.

Beginning in the 1920s fire towers were being built across the state to protect new growth after years of clear cutting by the tannery and lumber industries and a number of devastating forest fires. At one time 449 fire towers stood guard over the state’s forests, most of them built during the era of Gov. Gifford Pinchot. The tower on Hause Hill was, not surprisingly, one of the first—with its sweeping vista to the east, it protected the forestland bordering Governor Pinchot’s ancestral home in Milford.

Gould’s Tower was built using teams of horses to carry the materials to the site. The tower has a steel frame set into solid rock—grey, blue and red stone can all be found on the hill. At the time there was an old farm road that skirted hayfields and pastures and went up to the top of the hill, but it was rarely used. The agreement with the state specified that they would build and maintain the access road.

The tower stands at an elevation of 2143 feet and overlooks portions of Wayne, Pike, Monroe and Lackawanna Counties and the valley of the Wallenpaupack Creek below. From the cab at the top you have an enormous view north, all the way into New York State. You can see the watershed and impounding basin of the hydroelectric dam in Hawley, built by the PP&L Co. in the mid-1920s. At the time the lake was built you could see it from the tower, but today you can see only glimpses of it because of the trees. To the east you can see Porter’s Lake and Promised Land State Park. To the west you pick up the mountain range that separates us from Scranton. The view to the south is all woods and limited to LaAnna and the northern fringes of Monroe County.

A power line had to be erected not too long after the tower was built because they needed the electricity. When PP&L started to build the power line they hired my dad, and that was the beginning of his career with the company. And the beginning of my uncle Bill Hause’s part-time job as a forest fire warden. He served as fire warden from about 1930 until the tower officially closed more than 30 years later.

Uncle Bill’s duties were limited to the danger months, which are considered to be early spring and fall and not, as one might expect, the hot summer months. In summer the tree canopy holds in moisture and humidity and makes the forest resistant to burning. From late March to early May and then from about mid-September through October, Bill would be up in the tower all day, from 10 am to 6 pm. I remember he’d get down to the house about dark. After that, if there was fire someone would be able to see it.

The seven-foot-square cab at the top of the tower was sparingly furnished with benches and a small stove, and equipped with binoculars, maps and a telephone. Later they installed a radio for sending and receiving emergency messages, which Uncle Bill, being electronically inclined, fell in love with immediately. It was a good thing. I remember the forest fire warden at Camelback was called “Pocono Pete.” I’ll never forget that.

The most important piece of equipment was the alidade. An alidade is a horizontal circular map about three feet in diameter, mounted on a movable stand. Gould’s Tower is at the center of the map which has a radius of 26 miles. This is what Bill used to pinpoint the location of a forest fire. There was a horizontal copper tube across the map that he could rotate and look through. If he saw smoke he would look through the tube to determine the compass bearing and approximate distance. Then he would get on the radio and call High Knob Tower, and between the two of them they could triangulate to determine the exact location of the fire. Bill could estimate the type of fire from the smoke—heavy, black smoke indicated an oil fire; white smoke pointed to a leaf fire; and wispy, spreading-out smoke, moving fast, indicated a grass fire. Once he pinpointed the location he would call the fire company, and it wouldn’t take them long to get a fire under control. He always appreciated the cooperation given him by the volunteers of Greene-Dreher Fire Co., under the direction Fire Chief Charles Ehrhardt.

Bill was in constant touch with other forest lookouts, places like Elk Hill, Salem Mountain, High Knob, Buckhorn Ridge, Dry Meadow, Dancing Ridge, Scrub Oak, Tark Hill, Pine Hill, Big Pocono, Water Gap, Pohopoco, Stony Point, Dry Meadow Hill, Fox Hill, Penobscot Mountain, Harveys, Mehoopany, Ricketts, Shickshinny and Freeland. These were among the dozens of fire towers in active use at the time within the Lackawanna State Forest District, all under the supervision of Superintendent of Forest and Waters Manny Gordon in Scranton. [The district was rededicated Pinchot State Forest District in 2016.]

In times of severe drought Bill would stay overnight in the warden’s ground cabin. There was a cot, a table, a telephone, a small wood stove, a small kerosene heater, a corner cabinet and a rake with triangular tines that was issued by the state as your firefighting weapon. When I first saw it I thought Bill had made it, but I found out later by going through some of the books that it actually came with the tower. There was also a water tank that you could put on your back and it had a hose you could squirt. If that hill caught fire the rake and the little squirty thing were not going to do much good. The large numbers on the cabin roof were so planes going over could identify their location.

William Hause was educated at Hopedale School in Newfoundland and later took evening classes at Drexel Institute of Technology where he studied to become an electrician. He returned to Angels in the early 1900s and went to work for Clearwater & Hutton, a pioneering electrical company with offices in The Arcade building in Scranton. One of their clients was the Lyceum Theatre on Penn Avenue, and Bill had the opportunity to operate the lighting system for shows featuring Ethel Barrymore and other stars. He often talked about that. During World War I he worked on the design of portable fluoroscopes for use in Base and Field Hospitals treating American soldiers. After the war he helped electrify the new buildings for the Lehigh Structural Steel Co. in Allentown, and in 1939 he helped put up the buildings for the New York World’s Fair. During World War II he worked at Bethlehem Steel. Wherever his work took him, Bill arranged his schedule so he could be aloft when the danger seasons came in April and October.

When Bill was in his 80s he and his little dog Buddy would spend the day together in the lookout. It was a good place to be on a hot day. But on most days it could be downright cold and he would wear his camel’s hair coat and warm boots. In a persistent wind the structure would sway back and forth with a rocking motion that he said required a set of “good sea legs.” Among his many talents, Bill was a gardener, wood carver and artist who worked in oil, watercolor, charcoal and pastels. He did a lot of paintings, including of the tower and ground cabin, and gave most of them away.

We came into possession of the tower by accident. It was decommissioned around 1967 and the state was going to tear it down. My parents, my brother and I didn’t want to lose the tower, it’s part of our family history. The state was accepting bids, and in 1976 Mom and Dad made an offer and we ended up owning the tower. In spring and fall I still go up there two or three times a day just to make sure there are no fires.