By Melissa Burdick Harmon

All my life, I have been eager for the next adventure to begin. And so it happened that I arrived at what was then called Hahnemann Hospital in Scranton on August 7, 1950, quite a few hours before I was expected. I was the first in my family to be born in a hospital. My parents had saved up, in those pre-health-insurance days, so that the boy who would be named James Arthur Burdick, after his paternal grandfather and great-grandfather, could be born in style.

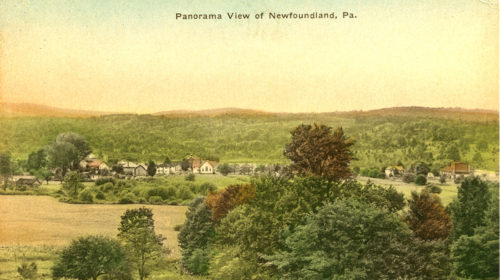

The word was that it would be a long labor. Dr. Lupcho waited until his office hours were over before starting in from Newfoundland to handle the delivery. My father strolled down to Preno’s to order the Blue Plate Special. My mother was alone in the room at 6:10 p.m. when I decided that it was time to see the world. “Nobody delivered you,” my mother used to say. “You just arrived.” My father returned to learn that he probably hadn’t needed to blow all that money on a hospital birth, and that he might want to consider a name other than James. In due course, now named Melissa, I arrived in Newfoundland, to the big white house that had originally been purchased by my great-grandmother, Lucy Robacker. There, my parents, Bob and Jean Burdick, my sister Jean Mary and I lived on the south side of the house while my maternal grandparents, Friend and Minnie Robacker, lived on the north side.

About Our Family

According to family records, my mother was a descendant of Christoph and Elisabetha (Schafer) Rohrbacher, who emigrated with their children from Baden, Germany, in 1824. My maternal grandfather, Friend Robacker (the spelling of the last name was changed), married his wife, Minnie Corey, in what the local newspaper described as a “very pretty wedding” . . . “followed by a sumptuous repast” on September 25, 1907. She was from Tresslarville, near Lake Ariel, and taught in the two-teacher Maplewood School. As my grandfather loved to tell it, he was driving along in his horse and wagon, saw Minnie outside calling her students in from recess, thought she was the cutest little thing and went over and “washed her face with snow.” She married him anyway.

My father was a direct descendant of Robert Burdick, who left England for Rhode Island in 1651, and his wife, Ruth Hubbard, whose great-grandfather Thomas Hubbard was one of the 300 Protestants burned at the stake by Mary Tudor. The descendants of Robert and Ruth were Seventh-Day Baptists, and many of them moved to Susquehanna County in the early 1800s. From there my father’s family made their way to Carbondale, where they became plain, garden variety Baptists. My parents met when Becky Burdick, my mother’s classmate in nurse’s training at Moses Taylor

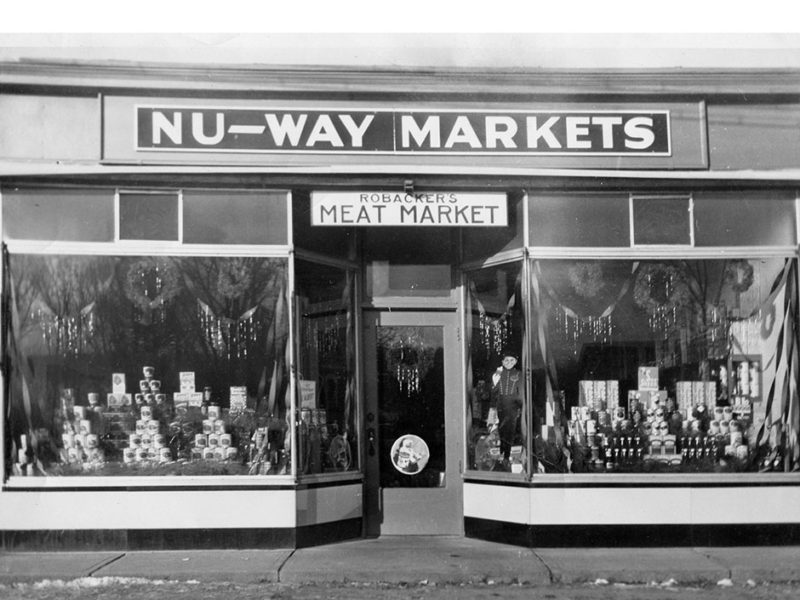

Hospital, fixed her up with her brother. It was a success. Although it was strictly forbidden for student nurses to marry in those days, my parents were secretly married in a Baptist Church in Newark when my mother was doing specialty training at New York Hospital. She always joked that she went directly from the wedding ceremony to night duty in the hospital’s maternity ward. She continued to live in the nurse’s residence until she earned her RN. They moved back to Newfoundland not too long after, and my father joined my grandfather in his GLF feed business, located right next to our house. My sister, Jean Mary, was born in 1943.

Hanging Out With Grandpa

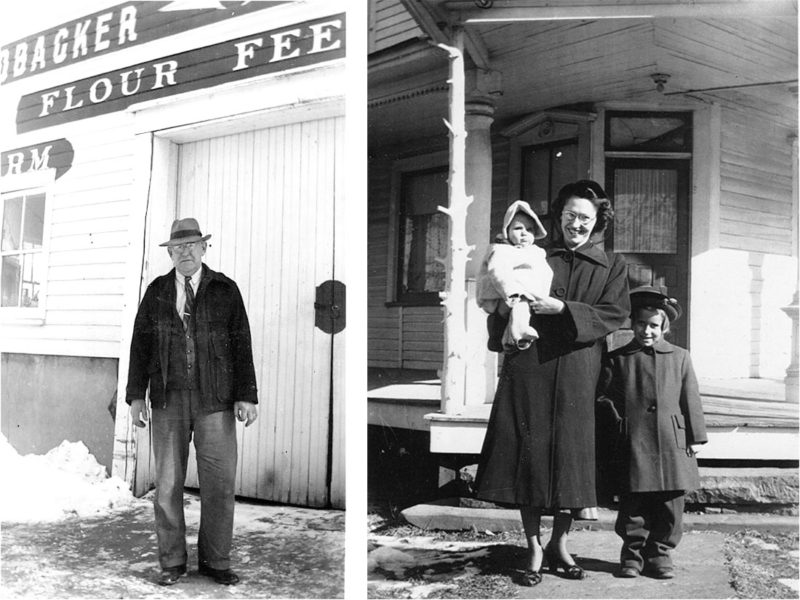

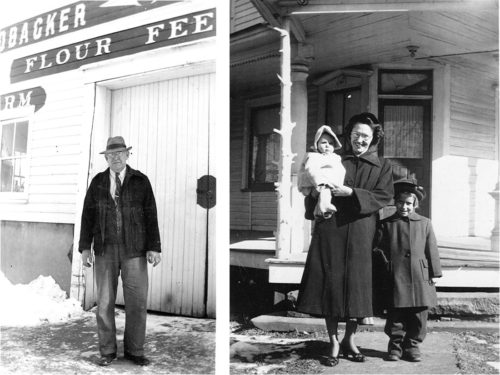

By the time I was born, my sister was about to enter second grade, so I was the only kid home during the day. But in 1953, my Grandpa Robacker retired from the feed store—the big green “Robacker and Burdick” over the door was repainted to read “J.R. Burdick – Flour Feed Grain Farm Supplies”— and I had it made in the shade. Grandpa had endless time and patience. I spent many hours sitting by the old coal stove in their kitchen, while he puffed on his beloved Lucky Strikes and told me stories that he made up from scratch. He cut out pages and pages of paper doll clothes for me, and on special days, he would make popcorn, shaking an old wire popcorn popper over the hot stove and covering it with about a pound of homemade butter. When he would deliver feed to help out my dad, I rode along. On the way back we would always stop at Dietz’s or Gilpin’s Drugstore for some secret “don’t-tell-your-mother” ice cream (frequently purchased about 15 minutes before supper). Wherever the two of us went, Grandpa would find someone to talk to. I think everybody in Wayne and Pike County knew Friend Robacker.

Waiting to Go to School

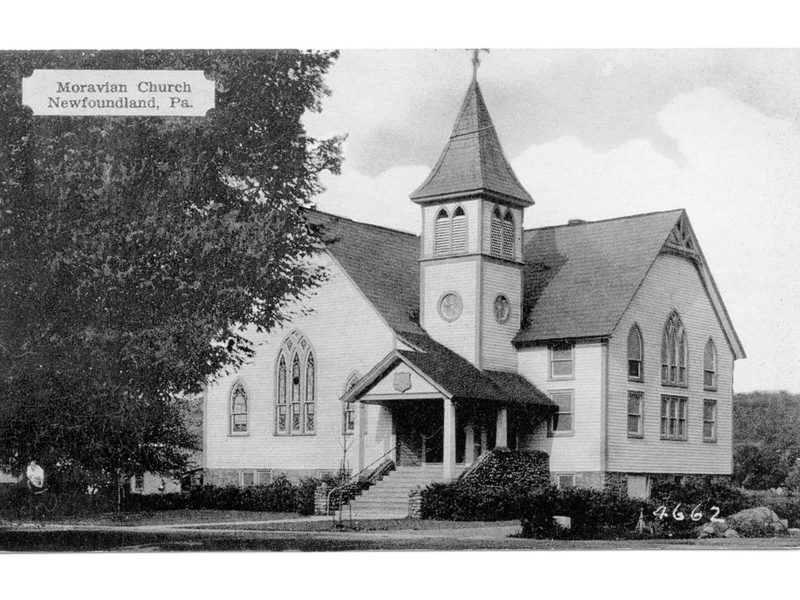

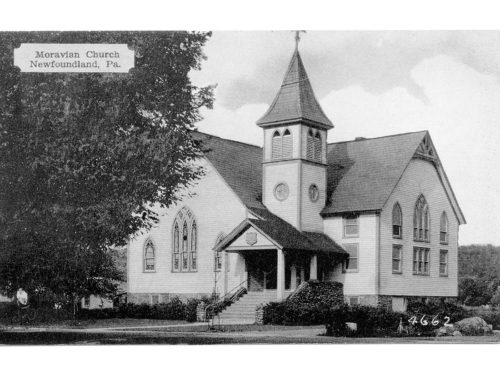

Pre-school life in Newfoundland had a gentle rhythm. Kids started looking forward to the Carnival in May and to the GDS Fair the minute the carnival rides left town. There was Sunday School at the Moravian Church, where I was in a class of boys—1950 was a banner year for boys in Newfoundland: Craig Beesecker, Gary Voeste, Bobby Robacker, Gary Gilpin, Jimmy Fetherman, Jimmy Gilby. The Sunday School picnic at Promised Land was another big deal—all the Canada Dry Spur and chocolate-vanilla-strawberry ice cream bricks you could hold, plus you could usually stay in the lake until you turned blue and nobody would make you come out.

On Thanksgiving Day 1954, however, something truly wonderful happened. Ed Parsons arrived, climbed up on the roof, put up an antenna, and we had . . . television. Of course, it was Thanksgiving Day, so our only station, WNBF Channel 12 Binghamton, was airing a football game. There wasn’t a single person in our house who was remotely interested in football, but all six of us sat there and watched it as if it were the Second Coming. I swiftly became Queen for a Day’s biggest fan. I would wander out to the kitchen and ask my mother, in the sonorous tones of host Jack Bailey, “How would YOOOU like to be Queen for a Day?” She usually said she wouldn’t mind. I was also mad for Drazen’s City of Fashion, a local Binghamton show that always ended with a model wearing a wedding gown.

Life wasn’t all glamour, however. I had a job, which was to help feed the chickens in the coop attached to my father’s store. The baby chickens came in the mail, brought to the Newfoundland Post Office by a rather frightening looking man whom we kids called Monkey King (behind his back, of course; I think his real name was Frank Jones). He brought the mail in from Scranton in a black vehicle that looked eerily like a hearse. The baby chicks arrived like little puffballs of cuteness, but very quickly, I learned time and again, they became terrifying, swoopy, pecky, flappy individuals that dive bombed the hand that fed them. I loathed them with all my heart. Most Saturdays, my father would kill one, and I would watch in horrified delight as it ran, headless, around our back yard. My mother would spend most of the afternoon plucking and dressing and pulling out the unformed eggs, so we could have roast chicken for Sunday dinner. Many years later, when I was in a hacienda high up in the Andes in Peru, on a magazine assignment, chicken was served for dinner. I tasted it, and a flood of memories rushed back. “Oh, my goodness,” I said. “THIS is what chicken tasted like when I was a child.”

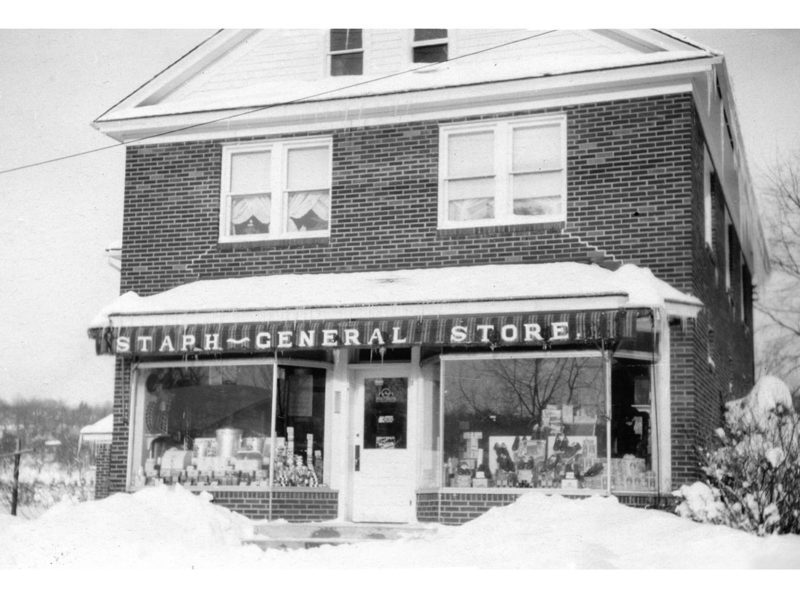

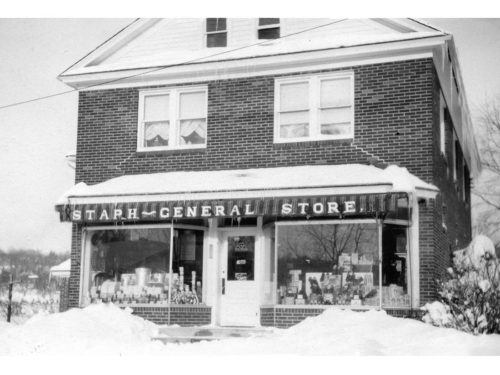

My allowance was a quarter a week (earned by being dive bombed), which went a long way at Miss Ella’s penny candy counter. She stocked chocolate squares that were so good I still measure chocolate against them. They somehow picked up the musty smell of the store, which only enhanced their flavor. There was red licorice, of course, and in summer, gumdrop watermelon slices. Every once in a while Miss Ella would get in a specialty item, and word spread fast. I remember a couple of days when every kid in town sported giant wax buckteeth.

I can see Miss Ella now, in a lace “Sunday dress” and high heels, her hair perfectly marceled in the style of the 1920s, makeup in place, sitting by her potbelly stove waiting for customers. She sold everything from clothes to canned soup to tools. She stayed open late one night a week for out-of-town shoppers. We kids all thought she was fabulously wealthy and had money secretly hidden all over the store. I don’t know if she really was rich, but she certainly was every inch a lady.

The World Changes

In August 1955, I turned five and received a Davy Crockett inner tube and coonskin cap, and a pair of bright yellow sneakers. I thought those sneakers made my feet look like two sticks of butter. I loved them.

A couple of weeks later, it started to rain. My mother called me over to the screen door and said, “Look, Lissa, the ‘little men’ are walking.” That was her way of describing rain that came down so hard it made bubbles on the road. But this time the rain didn’t stop. By night, it was looking serious. Jean and I were put in the double bed in one of the spare rooms, and were told to STAY THERE. I put on my coonskin cap and kept my Davy Crockett inner tube right by my hand, just in case. I remember hearing my parents running up and down the stairs, carrying furniture to the second floor. It was an endless night. When morning finally came, the sun was out, Hurricane Diane had turned into the Flood of 1955, and my secure world—where nothing ever changed—was gone forever.

For days, we kept hearing about deaths. We were luckier than most. The Greens’ barn door (the farm behind the Newfoundland Hotel) had settled against the front of our house, which kept the water somewhat at bay. My father’s feed store, however, was basically destroyed. He moved the business to a building he owned up the road, where the saw mill now stands. It is only as I write this that I wonder about the fate of my archenemies, the chickens. In all the excitement, I had completely forgotten them.

We couldn’t drink our water, and didn’t have a lot of food on hand, but the ever-resourceful Grandpa Robacker would disappear and reappear with something . . . a milk can full of potable water . . . somebody’s homemade cheese. Plus, Miss Ella opened right up and we bought canned goods from her. Then of course, there was the day the helicopter flew in with much needed supplies and landed right smack in Miss Ella’s field. Every kid in town was on hand for that. My sister ran so fast she lost one of her shoes in the flood mud. My beautiful yellow sneakers became permanently mud brown.

School at Last

For what seemed like centuries, I had been hearing, “Before long you can go to school and learn to read.” I don’t think I have ever before or since looked forward to something as much in my life. Finally, the day came. There were 36 children in my first-grade class, and dear Mrs. Carlton was not young, but she had us all reading and printing, adding and subtracting by the end of the year. I remember the thrill of that first day when she handed out sheets of yellow paper and crayons and we got to draw. It was wonderful. A few days later she passed out our first reading book, called Splash! The time had finally come. I was going to learn to read! Wild with excitement, I opened to the first page and discovered . . . that I could already read, at least well enough to read Splash! My mother read to me a lot, and I guess I had been following along without realizing it. It was one of the biggest let downs of my life.

On a soft June evening in 1958, I was hanging out on the front porch with Grandpa. He was helping me solve a kid’s crossword puzzle, when, to my utter amazement, two new girls appeared in the front yard. It was a rarity back then ever to see someone you didn’t know. They said that they were from Germany, and their names were Barbel and Marita. In broken English, they explained that their father had come to work on a project at Tobyhanna. They were renting part of Julia Sieg’s house, up the road. I couldn’t believe my luck. New kids! Foreign kids! Kids with accents! I took off like a rocket to show them our back yard. Not five minutes later, my sister came outside to tell me that Grandpa Robacker had died. Just like that. He was still there on the porch, my crossword puzzle at his side, his last Lucky Strike still burning between his fingers. He had had a heart attack and simply slipped away—an easy death for an easy-going man. The day after the funeral, I sat in Miss Stackhouse’s second grade class, looking out at the trees in front of the Moravian Church and thinking, “I wonder if there will ever be a day when I don’t miss Grandpa?”

Summer vacation began a week later, and everyone on my side of the house was working—my mother at the Post Office and doing private duty nursing, and Jean as a waitress at The Brookside in South Sterling. And I had lost my best friend. My grandmother valiantly tried to fill the void, but she didn’t even know any silly riddles, and she always let me win at checkers. Grandpa would have given me a run for my money. Grandma Robacker and I did have a regular date, however, to watch her two favorite TV shows, Liberace and The Lawrence Welk Show. We never missed. I was a great fan of the Lennon Sisters, especially the youngest one, Janet, who was just my age. Many years later, I was sent to Branson, Missouri, to do a magazine story, and I interviewed the Lennon Sisters. Somewhere mid-question, I found myself screeching to a halt. “You know,” I said. “My grandmother would not have known what to make of this.”

Friends

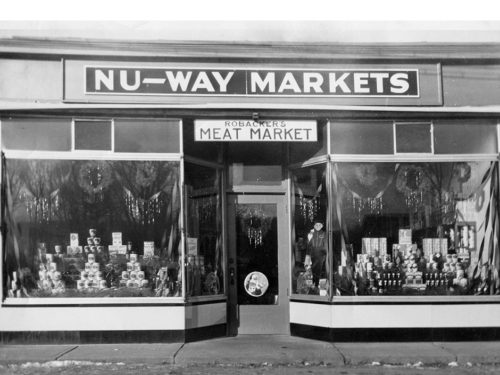

Once I started school, I got to know some girls, in addition to the usual crew of Sunday School boys. I spent a lot of time hanging out in Dutch’s Market, with my best friend Gail Butler, daughter of Dutch and Betty. Gail and I didn’t have a lot of toys, but we had good imaginations. One day we were playing “Washing Machine” in one of the store aisles, a game that simply involved spinning around as fast as we could go. We were well into the rinse cycle, whirling like dervishes, when Gail threw up all over the canned soup section. She was my dearest friend, but I was so relieved that she had spoiled the Dutch’s soup selection and not me. After that, her parents suggested that we might like to play some of our more imaginative games outside.

I could also frequently be found at the Wohlfart’s, playing board games with Peggy and cadging snacks from her mother, Ethel, who was also my Brownie Troop leader. They lived two doors down from ours, and I was in and out of their house as if it were my own—I don’t think it ever occurred to me to knock. Ethel always gave a warm welcome.

Music Lessons

Around that time, to my horror, my mother decided it was time for me to take piano lessons from Miriam Ehrhardt, who lived a short distance up the street. Miriam basically had a monopoly on the piano lesson industry in town. It seemed like a natural. My mother was quite musical and had taught piano lessons herself years back. My sister, at 14, was already playing the organ at the Moravian Church. Nobody ever gave a thought to the fact I tended to take after my father, who was famous for singing “Happy Birthday” in a monotone. Instead, I longed to take tap lessons with Gail, who was learning to step-shuffle-step-step from Lucille Strupcewski, the music teacher’s wife.

My mother wouldn’t hear of it. Gail gamely tried to teach me the steps to “Shuffle Off to Buffalo” on the old tennis court behind the school, but in the absence of tap shoes, not to mention music, it was a limited success. So, every Tuesday after school, I plodded up to Miriam’s. I swiftly caught on that she loved a good laugh, and I spent far more time collecting jokes for my piano lesson than I did practicing. She kept a notebook for each of her students, which reported progress and outlined what should be practiced. Students got gold, silver, or red stars, depending on performance, but Miriam hated to give out anything but gold. I used to tote home a notebook that read, “Absolutely last chance gold star,” followed the next week by, “Absolutely, positively last chance gold star,” and so it went.

Every summer, Miriam’s students performed in a recital at the Moravian Church. We were required to memorize our pieces, which wasn’t hard. We also had to play them correctly, which was here I hit trouble. One year, I played a duet with Ellen Cramer, which was quite stressful since her father, the school principal, was in the audience. We pounded away—Ellen was actually quite good. I remember vaguely wondering where the B flat key had gone as I performed, but on I rolled. Only later did I learn that I had played the entire piece with my right hand one note too high on the keyboard. The good people of Newfoundland applauded loud and long anyway. My father applauded loudest of all. But then, I suppose he hadn’t noticed that there was anything wrong any more than I had.

Special Times

In Newfoundland in the 1950s, there was always something to look forward to. Fall brought trick or treating, and kids just went on their own—no parents allowed. There was always a good haul of candy (and the occasional highly disappointing apple). My favorite stop was Earl Fetherman’s. Earl lived with his mother, Ollie, in the little house just south of the Wohlfart’s. When ghosts and witches came to call, he would bring out a giant penny jar, and you could reach in and keep as many pennies as you could grab. Sometimes, if you had a small hand and looked wistful, Earl would even let you double dip. Given that in those days ten pennies could get you the latest Little Lulu comic at the drugstore, trick or treating at Earl’s could set you up for weeks.

December brought practice for the Moravian Christmas pageant, which was a big deal back then. I was always cast as the Narrator, to avoid any further musical missteps. The abundance of boys my age meant that there were always lots of available shepherds and Wise Men. The candlelight service that followed was, and I am sure still is, quite lovely. And then you got to go home and lie awake all night, wondering if you had gotten what you asked for and if—wouldn’t it be wonderful?—it would snow in the night.

Whenever it did snow, every kid in town would head for what was then called Hecker Hill, before it went up market as Crestmont Drive. Nobody called each other to make plans. Kids would just show up, pulling their Flexible Flyer sleds behind them, trying to get as many runs in as possible before the cinder truck came through. When it was dark, it was utterly glorious—whooshing down those hills head first, looking at the glimmer of the street lights in the village below, and hoping against hope that school would be called off the next day. There isn’t a ride at Disney World that can equal that for excitement.

Summers

Summers in Newfoundland were wonderful—unstructured and unsupervised. My only requirements were that I had to be home by dark, and if I were eating at somebody else’s house, I had to call. Play dates and programmed activities had not yet reached the greater Newfoundland area. We always found something interesting to do. I was quite small when my sister Jean, Peggy, Barbara, and I went into show business. Two summers running, we put on the “All Star Variety Show” on our back porch, which had no rail and did, more or less, resemble a stage.

Jean and Peggy played flute duets. Barbara performed a ballet, using a crinoline for a tutu. We made up soft shoe routines. I was not allowed to sing, but got to recite poems and act in skits. I also had to make a very quick change into my blue pajamas, to become the “The Little Blue Man,” a character in a popular song of the time. I think my sister recited the song, at the end of which I had to disappear, in accordance with the lyrics. That meant jumping off the porch, which was taller than I was, and landing on the flagstone sidewalk below. There’s no business like show business. Most of Newfoundland attended these carefully rehearsed productions, and actually paid to do so. We were even mentioned in “Newfoundland Notes” in the Scranton Times. We must have been absolutely terrible, but boy was it fun.

We also had movies at the old Haubert Theater in Newfoundland in the summer, and the rule in my house was that if I could come up with the quarter for the under-12 admission, I could go. (My allowance was up to a dollar by then, with no chickens involved.) I usually went by myself, though in truth, Jean was often there with her friends. In the beginning, I was so short that the person at the ticket window—I think it was Miss Waltz, the third-grade teacher—couldn’t see me. My father would go in and pay with my quarter, and then come back to pick me up later. When the movie South Pacific came it was the most fabulous thing I had ever seen. I went all three nights. Everyone in town went, even Miss Ella, who had never before in recorded history gone to the movies. When the movie musical Gigi came to town, that same summer, even my grandmother bought a ticket. I think it was the only movie she ever saw, except for Mrs. Miniver.

One glorious summer day when I was nearing ten, my mother said, “Go out on the front porch and watch for your father to come walking up the road.” I thought she had lost her mind. My father never walked anywhere, and besides he was at the feed store. But out I went. And sure enough, in a couple of minutes he appeared around the curve in front of Woltjen’s Lumber Yard, pushing the brightest, bluest, most beautiful girl’s bike that I had ever seen. It had been on sale at the Western Auto, and it was an early birthday present. It was my ticket to ride and I had places to go.

Of course, I didn’t have the faintest idea how to ride a bike, but word spread fast in Newfoundland back then. Very soon, Lynn and Craig Beesecker materialized, to give me a bike-riding lesson. A little over an hour later, I was able to wobble up to the feed store to show my bike mastery to my father. (When I mentioned this to Craig at our recent 40th class reunion, he did not have the faintest memory of his role in this major, lifechanging event. You never know how important small actions can be in the lives of others.)

I rode everywhere. Down to Greentown, where Jean Ann Lupcho was teaching swimming lessons in the creek, never mind that a few of Fred and Alice McLain’s cows would also be standing in the creek about 100 feet away. Over to visit Gail, who had a new croquet set. I even used to ride up to the Pantry Shelf in South Sterling, where my sister had a summer job as a waitress. That was quite a haul, but the expectation of Maudie Gillner’s homemade, ten-cent brownies, kept me pumping away. On the way back, if you worked it just right, you could make it all the way from the South Sterling Methodist Church to the Odd Fellows Hall in Newfoundland without pedaling even once.

Wings on My Feet

My father always loved to travel, though he could only get away from the feed store for about four days at a time. He always took us somewhere exciting, every year. The year that we went to the Jamestown Festival, I had given my beloved doll, Sylvia, a bath the night before we left. I noticed the next morning that she seemed to have put on a little weight. She was, in fact, utterly waterlogged. We had to stop every 20 miles or so to wring her out. She was still dripping a little bit in the Palace of the Governors in Williamsburg. It was a grand trip. But now I think of my father’s precious four days off, and marvel at his patience.

One day, he came home from the feed store and announced that the Erie-Lackawanna Railroad was offering an excursion (I remember being quite taken by that word) to New York City and we were going to go. We went to look at the gems at the Museum of Natural History and climbed up the Statue of Liberty, all the way to the top of the torch (one member of the party had to be carried). We saw a show at the now-long-gone Roxy Theater, where people performed the miracle of ice skating on the stage. We pulled sandwiches out of the little doors at the Automat. And I walked down the street like I had wings on my feet. I had found my home.

My wanderlust arrived early and has never left. I used to walk home from school and look at the hill behind our next-door-neighbor Helen Feigel’s house, and think “I’m going to get over that hill. I’m going to SEE THE WORLD.” (Never mind that if I had ever achieved the goal of getting over that specific hill, I would have wound up in Panther.) I pored over my father’s National Geographics and made lists of all the places I would visit. I wanted to travel so much that I used to pretend I was taking trips in our house. I would pack my sister’s blue cardboard suitcase and go into one of the smaller spare bedrooms, which was the train car. I would then move into another spare bedroom, which was the hotel. I would take a tour of the back yard. My mother, however, drew the line when I asked to order off the menu at supper.

I couldn’t wait to get out into the big world. Not that I didn’t love Newfoundland. I did take it for granted though. I had no idea how precious it was to live in a place where everyone knew you and praised you for your small victories and kept an eye out for you. People were kind in ways that seem remarkable to me now. It was somewhat accepted that if you were out and about in town, some adult or other would watch out for you. I remember once when Gail and I were riding our bikes, and I took a really bad spill. There was blood everywhere. We simply went to the nearest grown-up, who happened to be Marion Phillips, and she stopped whatever she was doing and picked gravel out of my leg for about 20 minutes and bandaged me up. I said thank you and we went on our way.

Making Changes

In the early 60s, major changes came to our school in Newfoundland, as we Greene-Dreher kids had to bid goodbye to more than half our class (our numbers dropping from a once mighty 36 to just 19, including only four girls). The students who came from Sterling Township would go to Lake Ariel for the rest of their schooling. The rest of us got word that we would be going to the new Wallenpaupack High School in Hawley when construction was completed. We finally made the move in February 1964, which was, for me, the middle of Eighth Grade. Lucky for us, our high school teachers came with us. We still had Mrs. Edwards for Algebra and Mr. Parsons for Physics, and Mr. Arneberg taught us all how to drive. Even luckier for me, my mother became the school nurse for all of the elementary schools in the district, so she could often drop me off at the high school.

On our last day in Newfoundland, Gail and I went over to say goodbye to our grade school teachers. “It’s sad,” I said to Mrs. Snyder, my beloved fifth grade teacher, who had secretly let me take books out of her library from second grade on. “Nonsense,” she said. “It is a wonderful opportunity and you will enjoy every minute of it.” She was right, of course. It was a great adventure. But at the same time, we became little commuters, developing lives and friendships beyond our safe, small valley.

Gail and I were assigned to different homerooms and were enrolled in different classes. Peggy graduated and went off to college. My sister moved away. New friends edged out old ones. I too moved on. I did make it over the hill behind Helen Feigel’s house, went to Wilkes College and to graduate school at Columbia University, and achieved my goal of working as a writer in New York City. I thought I had left my small-town life behind. Over the years, though, I’ve learned that Newfoundland has long arms.

A Small Town with a Long Reach

One day, I was walking along Third Avenue in New York when I looked up and saw a familiar face coming toward me. You couldn’t miss that red hair. You couldn’t miss those freckles. “Sally?” I asked, not quite believing my eyes. “Yup,” she replied. It was Sally Fitz, who had been my classmate until the district split and she had gone off to Lake Ariel. I think the last time I had seen her had been in the Sterling Grange Hall where we used to whip through our Junior Grange meetings in record time, then sit and wait impatiently for the grown-up meeting to end so we could hit the refreshments. She asked me what I was doing, and I said I had left my corporate job and was trying to make it as a freelance writer. “Oh,” said Sally Fitz, “I work for a magazine and my boss hires writers all the time. I’ll introduce you.” What Sally failed to mention was that she worked for a travel magazine. I did meet her boss, and just a few weeks later I was on a plane to Thailand, my first of many hundreds of travel assignments for many different magazines, a career that would take me to all seven continents and almost every country. Thank you, Sally.

In 2002, when I was working as Travel Editor for Biography magazine, I was assigned to go to Antarctica. I boarded a ship in Ushuaia, at the very tip of Argentina, under cold gray skies. The next morning, I went to the dining room for breakfast, facing the usual dilemma of finding people to sit with without intruding. I saw two men sitting alone at a table and asked if I might join them. I introduced myself as Melissa Harmon. One of the men was wearing a cowboy hat, so, as a brilliant conversation starter, I asked if he were from Texas. “No,” he said, “I’m from Pennsylvania.” “I grew up there,” I replied. “Where?” he asked. “Oh, even if you’re from Pennsylvania you wouldn’t know it. It’s a tiny town in the Poconos.” “What town?” the man in the cowboy hat asked. “It’s called Newfoundland,” I replied. The man looked at me a bit oddly. “What was your maiden name?” “Burdick,” I said, as waves rolled and icebergs slid by the dining room windows. “Are you Jean and Bob’s daughter?” he asked.

The man’s name was Bob Robbins, and he had once rented a room from Abbie and Ray Robacker, directly across the road from the house I grew up in. He had married my mother’s close friend, Alberta Banks, and they had eventually moved away. He remembered my parents as a young couple. He remembered me as a baby. We developed the habit of going up to the top deck to talk. “Did you know Lawrence Grimm died?” he asked, as an iceberg the size of Hamlin floated by. “Yes,” I said, “my mother told me.” “They had the funeral dinner at The Rainetree. It was real nice,” he said. “Gosh, I remember when Bucky Drake built that restaurant,” I replied, as humpback whales arced around the ship like precision dancers. We watched huge albatrosses glide behind the ship as we chatted about how Elva Philips used to save Sunday papers for people in the drugstore and about when Ray Robacker kept cows. He spoke of my parents when they were young, with an endless future before them. And so we passed our days at the bottom of the world. Remembering Newfoundland.