by Diane B. Smith

Rohrbacker Gristmill — In 1824 Christoph and Caroline E. Rohrbacker and their six children, the youngest of whom was five-year-old Franz, left Baden, Germany, and sailed for America. Their eldest son, Jacob, accompanied them on the journey, along with his wife, Christina, and their infant son. The Rohrbacker family was among the earliest to settle in the Wallenpaupack Valley, and over the next several years they were instrumental in the development of the area.

The Rohrbacker family settled on 100 acres along Mill Creek, near its confluence with Wallenpaupack Creek, where they established a farm and built a small gristmill. Although it is not known when the Rohrbacker family built their gristmill, in 1837 forty-three residents of the area petitioned the Wayne County Court of Common Sessions for a bridge to be built across “Mill Creek.” With the dedication that year of the new Hopedale Moravian Church in Newfoundland, there were more travelers along Newfoundland Road, including weekly mail service that arrived from Bethlehem by stage. However, the petition was denied. Travelers would continue to cross Mill Creek atop the Rohrbacker’s stone and earthen dam, which was wide enough to drive a wagon across. In 1871, residents again petitioned the county for a bridge, and this time their request was approved. A stone arch bridge over Mill Creek was completed in 1873.

When Christoph Rohrbacker died in 1853, his son Franz (1818–1894) inherited the land bordering Mill Creek on which the gristmill was located. Franz and his wife, Ellen Clements, built a stone house on the property, where they raised eight children. The date 1854 is carved into the cornerstone of the house, which still stands today.

The Rohrbacker gristmill was situated downstream from the homestead, 30 feet behind a rock embankment that had been built along the creek to stabilize its steep bank. Remnants of the building’s foundation indicate that the mill measured 24´ x 38’ feet. The foundation walls are rough-hewn native fieldstone, and their construction shows superior workmanship. They rose to a height of four feet above the ground, and there were wide apertures at the center of the east and west walls. The millrace entered on the east side and turned the horizontal wooden tub wheel located on the lower level.

Tub wheels were often used in rural settings for the grinding of grain because the grindstones could be easily attached to the vertical shaft. The wheels were relatively small, simple, and inexpensive to build. Power depended on the flow of the water, making them ideal for high velocity mountain streams like Mill Creek. As with the undershot wheel, the tub wheel had blades rather than buckets. The blades were attached to a vertical shaft at a 30° angle and enclosed by a round wooden tub. The water hit the paddles directly, forcing them to turn the shaft.

A masonry dam was constructed about 100 feet below a waterfall, creating a narrow millpond. The dam consisted of two parallel courses of stone, wider at the base, with rubble rock fill between them. Total length of the dam was approximately 90 feet, and it ranged in height from 8 feet on the north bank to 13 feet on the south bank. The top of the dam was 10 feet wide. To avoid overtopping the dam, a sluiceway was used to release excess water from the millpond.

A masonry raceway channeled the water from the pond to the millhouse, where it turned the wooden waterwheel and exited the other side. Around 1900, a riveted sheet-iron pipe served as the penstock, and a 35-foot section of pipe remains half-buried on the property where it was washed below the mill site during the Flood of 1955. Fragments of a steel-banded milling stone can also be seen near the mill foundation.

The gristmill was a “custom” mill, grinding grains for individual farmers. It probably had only one pair of millstones, and the flour would have been sifted by hand. Typically, the miller collected payment by reserving a portion of the grain brought to the mill for grinding. The usual toll in the mid-1800s was one-eighth for corn and one-sixth for wheat. Because the value of the mill products did not exceed $500 annually, the Rohrbacker mill does not appear on the Wayne County Products of Industry Census. Nor does it appear on tax records until 1888, when Franz and Ellen’s son Florenz Rohrbacker (1862–1921) was listed as the miller. The flour and feed ground at the mill that year was valued at $400. The mill continued to appear on the tax rolls until 1935.

The Rohrbacker mill complex also included a butcher house, located 60 feet southeast of the mill. A tail race directed the water from the mill, via a masonry tunnel, to the building. As its name implies, the butcher house served for the heavy work at butchering time, such as making scrapple, sausages, and even soap from the rendered animal fat. All that remains of the butcher house is the six-by-six-foot mortared stone hearth, with a chimney that rises to a height of ten feet.

When Franz Rohrbacker died in 1894, his son Florenz assumed ownership of “all of the buildings, machinery and fixtures therein on the north side of Mill Creek, used and operated as a gristmill.” Florenz is remembered by local residents as being “as honest as the day is long.” On inclement days the farmers would bring their grain to his mill, and it was a time for them to socialize and share the news.

The mill ceased operation when Florenz died in 1921. His son Allen Mead Robacker (who changed the spelling of his last name), once demonstrated how the mill operated for his new bride, Henrietta Schaller. In 1935, Angelina, widow of Florenz, sold the mill machinery.

For many years following the closure of the mill, neighborhood children used the millpond for swimming and ice skating. Eventually the dam was breached and today only the side sections of the dam can be seen on the north and south banks of Mill Creek.

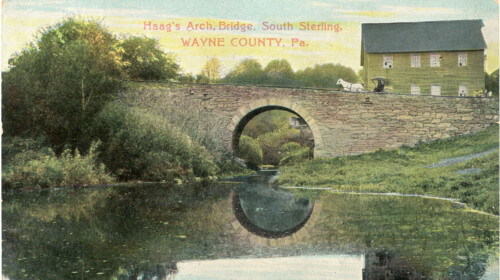

Haag’s “California Mill” — Johann Haag (1817–1891), known as John, emigrated from Prussia in 1853, residing for a short time in northeast Pennsylvania before traveling to the gold fields of California. The high Sierras beckoned to many a young man in those days who had a case of “gold fever.” For the next three years John engaged in placer mining, or panning, earning a sufficient amount to settle in the Wallenpaupack Valley and establish a prosperous business.

In 1857 he built a gristmill near the intersection of Newfoundland Road (Route 191) and Sand Cut Road (old Route 507). His “California Mill,” so-named because it was financed by his successful venture into gold-mining, was a four-story wood-frame building that towered above the creek. He married Louisa Rohrbacker, granddaughter of nearby mill owners Christoph and Caroline Rohrbacker. Shortly after their marriage, John and Louisa built a home across from the Haag Mill on Sand Cut Road. The original house was a two-room, hall and parlor house with a narrow staircase rising along the partition wall immediately inside the front entrance, which faced the mill. At a later date, the house was enlarged with a two-story addition, and its wrap-around porch with Victorian trim faced Newfoundland Road. John and Louisa had five children, including sons Maurice (1860–1944) and Alvis (1864–1917), who continued to operate the gristmill after their father’s death in 1891.

The Haag Mill measured approximately 26 feet by 40 feet, and rose three and one-half stories from a dry-laid foundation of ashlar (dressed) native stone. An enclosed waterwheel was located on the lower level, adjacent to the creek. According to family legend, it was either a tub wheel or an undershot wheel. In 1870 Haag reported that it produced 30 hp at the shaft and operated three run of stones. Because millstones could weigh as much as 2000 pounds each, they were located on the second floor of the mill, which was the entrance level. The maximum capacity of the Haag mill was 130 bushels of grain per day.

The third floor of the mill was where the grain was weighed and stored before being ground into flour. A mill owner typically reserved up to one-quarter of the grain as payment for his services. This is also the level where the ground flour was sifted and sorted. Since the mill did not contain an elevator, the grain and flour was lifted to the upper levels by means of a hoist system.

The dam and millpond were located about 300 feet upstream. The present-day remains of the dam show stone construction, wider at the base and extending 110 feet across the creek channel. The massive masonry structure was securely integrated into the bedrock cliff on the south bank of the stream, creating a narrow millpond with a fall of 24 feet. At a later period, the dam was reinforced at the center with wooden planks and a concrete facing.

The original millrace was probably stone-lined, and a sluice gate was used to start and stop the flow of water from the pond. The gate was opened during hours of operation and adjusted to control the flow of water past the wheel, depending on the number of runner stones being used. The mill was in operation about nine months each year, but during some of those months it operated only half-time. Milling ceased in winter when the creek and pond were frozen over.

The mill served both custom and retail markets. In 1860, with one male employee, they ground 2400 bushels of rye, wheat and buckwheat for flour and 400 bushels of corn for animal feed. Corn that was brought in would have been husked and left to dry for six to eight months before being shelled and bagged, ready for milling. In 1870, during six months of operation, 5,000 bushels of unspecified grains were ground at the mill.

In 1880 Haag reported that his mill was powered by a single water turbine, producing 17 hp. Production had increased to an average of 7000 bushels annually, and he employed two “skilled mechanics” who were paid $1.37 each for an eight-hour workday.

John and Louisa’s sons, Maurice and Alvis, learned the trade from their father. When their father died in 1891, Maurice and Alvis took over the mill operation. A three-foot-diameter riveted-steel sluice pipe, or penstock, was incorporated into the dam structure about six feet below the uppermost course of stone on the north side of the dam. The penstock directed the water to the turbine at a higher velocity than the earlier head race.

Maurice married Jennie Cummings (1879–1971) from Canadensis, and they resided on the family homestead. Alvis married Minnie Lancaster (1868–1947), daughter of nearby mill owner Reuben Lancaster, and they lived in the c. 1860 house on the south bank of Mill Creek across the creek from the mill.

By 1930 Maurice Haag closed the “California Mill” and dismantled the infrastructure and engaged in farming full-time.

Note: This article is an excerpt from Mills on the Wallenpaupack, published by the Greene-Dreher Historical Society in 2018 and available here.