An icehouse was a necessity on farms in the Wallenpaupack Valley in the 1800s. Ice was used to keep foods cool during the summer months, and the abundance of streams, lakes and ponds made it relatively easy for farmers to cut and preserve enough ice for their personal use.

On the William and Anna Manhart farm in Panther, ice was cut by hand on a small mill pond and hauled up to the icehouse with a horse and sleigh. Their son Arthur recalled, “Ice was brought into the cellar where a corner had been partitioned off to serve as a root cellar. They’d put the milk and food in there so it wouldn’t spoil.” In later years, William and his sons made an automated ice cutter out of an old car motor and a circular saw.

If a farmstead had a good springhouse ice might be a luxury. Milk and other perishables were kept in small springhouses where, in summer, the temperature ranged from 50 to 55 degrees. After the evening milking, the 20-gallon milk cans were immersed in the cold water until they could be transported the next morning to the Newfoundland Creamery. The Brown homestead in Angels had no natural spring so they dammed a small stream on the property to create a pond where they cut ice in winter. This allowed them to keep milk, butter, eggs, meats and other foods produced on the farm cool through summer and into fall.

Many farmers were fortunate to have a flowing spring adjacent to their barn; however, others had to have a milk house. Our milk house was unique as one half was an icehouse. That room was six feet deep and not quite so wide. The ice was harvested in winter and surrounded with sawdust for storage. That ice would keep for months and not melt. The evening’s milk was placed in a tank with lots of ice; the morning’s milk not. After the morning milking the cans were transported to the creamery in Newfoundland. —Virginia Rohrbacker

The Oscar and Annie Olsommer homestead in Roemerville had a good-sized icehouse that served their farm and general store. Gordon Olsommer recalled his grandfather cutting ice on Lake Wynooska: “They used hand saws and giant ice tongs to pull the cakes of ice out and slide them up onto a bobsled. A team of horses pulled the sled back to the icehouse, a timber-framed building about 20 × 30 feet, where the cakes were stacked and covered with sawdust. Later he used his old Model T as the ice tractor. The icehouse was no longer in use when I began to sprout up, but Aunt Pauline said when they were kids, it was a good place to sneak in and cool off on a hot day.”

Ice harvesting started right after Christmas and concluded when the icehouse was filled. The weather dictated the timing, and there were many preparations to complete before the cutting began. Old sawdust was emptied from the icehouse in late fall; the long, narrow-bladed ice saws were sharpened and the teeth filed and set to the correct angle so they would cut true and not stick and freeze into the cut; horses were shod with borium-tipped shoes to give them traction on the ice and packed snow.

After a stretch of bitter cold weather, when the snow glittered and squeaked underfoot, a hole was bored into the ice to measure its depth. First-frozen ice was best, and it had to be thick enough to support the team. Using a horse-drawn scraper, the surface of the pond was cleared of snow lest it insulate the ice and keep it from freezing to the desired depth. At six inches, the OK was given to the young folks that the pond was safe for skating. When the ice was at least twelve inches thick it was ready to cut.

The cutting and storing of ice was a cooperative effort among neighbors and families, and although it was cold, hard, dangerous work, it was a social activity that people looked forward to. Work crews were assembled and tasks assigned. The women provided plenty of hot food for the mid-day meal, and the men brought their homemade apple cider or elderberry wine to warm the heart as well as the body.

Friday, February 7 — Helped Fred Haser filling ice house, 4 hrs. Zada and I were there for supper and spent the evening playing cards.

Saturday, February 8 — Helped Fred Haser filling ice house, 4 hrs. Went to Lodge at night with Fred. —John Smith’s diary, February 1930

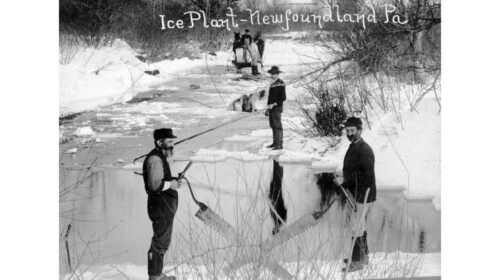

First, sight lines were laid out on two sides of the ice field, which was then marked off in a grid pattern with an ice plow that made a shallow groove. The dimensions of the grid determined the size of the blocks. Generally, they were about 12 × 24 inches, so that each block would weigh about 120 pounds. Since most farms had a team of horses for plowing, planting and haying, they most likely used a horse-drawn ice plow, pulling it back and forth along a grid line, with each pass sinking the groove three more inches until it was about three inches less than the thickness of the ice. If the ice were being cut for family use, it may have been cut by hand. Along the guide marks went the four-foot sawblades, setting free long rows called floats. The cakes were split off with a spud bar and, if done correctly, would break evenly, leaving no lips on the cakes. As the cakes were set free, they were guided down a narrow channel by men using pike poles and ice hooks to the place where the wagon or, if the ground was covered in snow, the bobsled stood waiting. Iron ice tongs were used to grip the cakes and hoist them onto the sled. The horses could be heard as well as seen when the bells jingled and the runners squeaked on the hard-packed snow on their way to the icehouse. Children and dogs often caught rides on the bobs or hitched a ride with their own sleds.

Icehouses were simple two-story structures built of rough lumber with board and batten siding and access doors on both levels. Usually, they were gable roofed, and sometimes they had two rooms, one for the ice and another for cold storage. Since air flow and dampness were impediments to the preservation of ice, drains were built into the base of these structures and small ventilators might be added in the roof to allow the escape of warm air.

Inside the building, a six-inch layer of fresh sawdust was spread over the floor. One layer of cake ice was put down at a time, leaving a space from the outside wall free and clear. As each tier was finished, sawdust was thrown around each cake so it didn’t touch it neighbors, and then the entire layer was covered with more sawdust. This would make it easier to separate the cakes later on. When the ice was stacked to within a foot of the ceiling it was finished off with a good two-foot layer of sawdust on top. Sawdust was poured and tamped down along the sides, creating a one-foot wall of insulation against melting. Although straw, leaves, bark or grass were used elsewhere, sawdust stood up best and was readily available in the Wallenpaupack Valley. Under ideal conditions, icehouses had a shrinkage of from 10 to 30 percent over the season.

When the ice on Lake Paupack was about 12 inches thick, it was marked off in blocks of 22 inches each. The blocks were sawed through and hauled to the icehouse on a sled drawn by a team of horses. Each block weighed about 150 pounds or more. They were raised up a slide by a horse pulling a rope attached to every seventh block by an iron spike. The horse soon learned exactly when to stop as the blocks reached the top of the ramp. The ice was packed in sawdust with 10 or 12 inches of sawdust separating the layers. The top was usually filled through a window. A larger icehouse was built by Elmer Newcomer around 1910 to replace the smaller one. In those days fresh milk was fetched in huge cans each evening from the Friebele farm, and ice cream was churned in quantity by hand on the kitchen porch—blueberry was the favorite. —Eleanor Webster

In the 1920s gas-powered engines increased the efficiency of the ice harvesting operation. This coincided with the growing need for ice by local hotels and boardinghouses; summer cabins and camp sites; creameries and general stores.

The icehouse at Mountain Breezes was about 16 feet by 24 feet. We figured out a way to make an ice saw powered by a motor and fixed it so we could put a belt on it to run a 30-inch buzz saw. It was on runners and had a handle so you could push it along the ice, raise and lower it. We used it to cut ice 12 inches by 12 inches, and we’d put a wedge in to break off the cakes. We used pike poles to push them up on the truck body to take to the icehouse at Mountain Breezes. —Ernie Bush

When Leon Heberling stored away ice in the icehouse at Sugar Hill Farm, it was cut on various ponds, including Meyer’s beaver dam pond in Panther. Leon had a motor on skids with a sawblade on the front to score the ice. A longer blade cut the blocks almost all the way through. He used a spud to break them apart and pull them out of the water, and ice tongs to load them on the sled and unload and place them in the icehouse. A layer of sawdust went on the floor, then a layer of ice, more sawdust, more ice, until it was full. The icehouse was at the back of the house and accessed from a covered porch. There was a built-in icebox against the wall for things that would spoil quickly, and a hall leading to an immersion water box where the 44-quart milk cans were stored. As the ice melted, the water ran through the water box to keep the milk cans cool until they were taken to the creamery. —David Meyer

Icehouses were in use on local farms until the end of the 1930s when modern electric refrigerators replaced the icebox. However, the need for ice continued on a small scale well into the 1960s—many of the cottages and cabins used by summer vacationers and seasonal hunters did not have electricity; tent campers at Ledgedale and Promised Land needed to replenish their supply of ice every few of days; summer camps for children abounded and oftentimes relied on old-fashioned iceboxes. To meet this need, Max Hazelton began cutting ice in the 1930s and selling it at his service station in Greentown, a side business he operated until his retirement in 1969. The story of Hazelton’s Ice is recalled by his son.

Ice Becomes an Industry in the Poconos

With the coming of the railroad to the Poconos, important new markets were opened up, not the least of which was the trade in frozen water. In the 1870s local businessmen formed ice companies to harvest ice off lakes and store it in huge icehouses for delivery the next summer to cities near and far. By 1902 hundreds of thousands of tons of ice were being produced each winter and shipped out in railroad cars, and it was still not enough to keep up with the ever-increasing commercial demand. Boxcar loads of ice were shipped to cities for use in family iceboxes, and ice was added to special “refrigerated” boxcars hauling fresh produce and meats. Some ice was even shipped to Florida for use in hospitals. During the summer when ice usage peaked, up to 150 boxcar loads per day shipped out of the Gouldsboro and Tobyhanna plants. At a cost of about six cents a ton to produce, the profits were enormous. Because of the success of this industry several man-made lakes were created and icehouses capable of storing upwards of 100,000 tons of block ice were built. Pennsylvania was the third-largest producer of ice in the United States, following New York and Maine.

The commercial ice industry employed over 250 local men on Pocono lakes each winter. Farmers would take their teams to work on these ice fields and stay until the harvest was finished. Many men stayed in one-room bunkhouses with 30 or more beds, and there were stables for the horses. It was a 24-hour-a-day operation with two twelve-hour shifts. At night, kerosene lanterns were used for light. The day shift started at 4 a.m. and the pay was between $4 and $4.50 a day for a man and team, plus room and board.

My dad heard of the ice harvest in Gouldsboro. This was about 1918. Someone told him they were hiring men and teams of horses. They had scrapers on the ponds to scrape the snow off, and the horses were hitched to them. Men would cut the chunks of ice and run them into the icehouses. The pay was $6.25 for the team and driver. The driver would get his bed and board, and the horses would get feed and hay. They would start in the last part of December or beginning of January and continue for about six weeks or more. Our father would not return home until all the ice was harvested. He liked it as the men would get together and play cards, and the food was very good and plentiful. He earned quite a bit of money for the time he was there. Later on my two brothers, Anthony and John, worked there for 35 cents an hour. They did this for many years, until there was refrigeration. —Pearl Cykosky

Many of the large Pocono Mountain resorts built around the turn of the last century were open year round and had their own icehouses which they filled with ice taken from their own lakes and ponds. An amateur film from 1919 shows Ice Cutting at Pocono Manor Inn—a labor intensive process for both men and horses.

Ice harvesting eventually became the victim of its own success. Industrialists grew impatient with the unpredictability of natural ice—the winters of 1878, 1890 and 1900 were considered “crop failures” when the ice never froze to the depth necessary for harvest. The advent of mechanically produced ice, which they claimed was “cleaner” and cheaper to produce, led to the decline of the ice empire. While home delivery continued for a time, by the end of the 1930s it too declined. The ice harvesting industry continued on a smaller scale in the Poconos until about 1950, and continued to offer wintertime employment to local men.

I put in a couple of winters on the ice pond in Gouldsboro. They put up ice there for a good many years. It’s a big job, a tremendously big job. Hundreds of people worked there. Everybody in the wintertime would wait for the ice plant to open so they could go to work for two or three months and make a little change. It took a lot of men to work on the ice. It was more or less dangerous work. At that time, they did everything they could with horse power. Farmers would take their teams over there and use them to plow the snow away. They had to scrape the snow off the ice, otherwise the ice wouldn’t freeze very thick. Snowplows were pulled by horses, and every once in a while they’d get a horse team in the water. They’d have a job to get them out. But they’d get them out. They’d get a long plank, put it in, get them up to the edge of the ice and pull them out. I know of one horse that Ed Adams had and that one perished. But very, very seldom did they lose a horse. I had a brother-in-law who was the boss over there, and I got a job on the chain, pushing ice off when they were putting it in the house. Chains were used to move the ice up into the gallery. The big chains were run by steam engines, and they were kept running and running. The ice was put up in these big rooms, and they’d have six or eight rooms putting up ice at one time. You would alternate pushing off the ice—if there were six rooms, you’d take every sixth cake. In the houses the cakes were spaced in rows six inches apart and covered with sawdust and hay, and they would hold like that until the next winter. The ice mainly went to New York for retail sale. —Burton Carlton

There was an ice business in Gouldsboro, and it was a wintertime job for a lot of people. They cut ice on three different ponds, and each operation had its own set up. They hired Stanley Peet who had a power cutter on an engine to cut ice. Then they had teams of horses that pulled the big floats in. They had a guy there who would snap back the cakes, and the cakes would go up a conveyor and across to maybe six or eight houses. They had a pusher up there, and he’d push the ice off the conveyor. If you were filling six houses every sixth cake would come to you, if you were filling three, you worked a little harder. I can never forget Al [Albert] Smith and Red Hibbs because they were tough pusher bosses, tough but good. When the ice came down the chute into the icehouse, a guy was there at the bottom with a pike puller. He’d get that cake of ice and swing it your way. If you had a good switcher, he would switch it right in place and all you had to do was catch a corner of the cake. I’m talking about cakes that were half as big as this table, big chunks of ice! If you got him mad or something, then you had to work to get it where it belonged. The best switcher I ever had was John Whittaker. —Willard Newcomer

Annual Ice Harvest Demonstrations at Tobyhanna

The Coolbaugh Township Historical Society Tobyhanna holds an ice harvest demonstration on Millpond No. 1 in Tobyhanna every winter to share an important part of their history. Volunteers and visitors have the opportunity to use a 1919 Gifford Wood Company power ice saw to lay out and score a large ice field before commencing to cut through two-thirds of the ice thickness. They then cut the individual 22 by 22-inch ice cakes with hand saws and move them through a channel to a ramp along the shoreline. Horses pull the ice cakes up the ramp, and workers pack them into the icehouse. The icehouse holds about 50 tons of ice and is located at the same site where a 60,000-ton capacity icehouse stood a century ago.